As part of the 2022 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands, Hearts&Science's Lysette Jones argues that if we do not take steps to understand how small brands can break through the hold that big brands have over them, then as citizens we will continue to be vulnerable to monopolistic behaviour and big business agendas.

We have never been more knowledgeable about the tenets of brand building. A great body of evidence supports building mental and physical availability through consistently reaching all light buyers of a category (Sharp, 2021). Emotional advertising aids memorability (Nicks and Carriou, 2016) and campaigns that aim for fame have larger business effects than those that don’t (Binet and Field, 2017). We even have a very practical methodology for determining the optimal split between brand building and sales activation investment (Binet and Field, 2018).

Yet, the world we live in is shifting rapidly. Consumers’ changing expectations and behaviours are affecting the ways in which brands can be borne and built. Complexity and choice paralysis has increasingly become the norm.

I believe that the well-established conventions of brand building are most relevant for mature businesses: where incremental gains are small but steady, and this pace aligns with shareholder expectations. Translating theory into action is more straightforward as efforts are building on existing brand equity and base that were formed during simpler times. As Ebdy states, “the single biggest factor in successful brand marketing is already being big” (Ebdy, 2015). I believe that there is a widening gap between accepted principles of brand building, specifically creating fame and salience, and the practicalities of how we do that in the modern landscape. This increasing division is most felt by smaller brands, who find conventional wisdom challenging to implement and are at risk of stagnation and failure.

I further believe that if we do not take steps to understand how small brands can break through the hold that big brands have over them, then as citizens we will continue to be vulnerable to monopolistic behaviour and big business agendas.

In this essay, we will:

- Analyse what fame means in a modern context

- Explore the implications for small brands

- Examine how small brands can aim for fame and what it takes

Increasingly elusive fame

Have we seen the last of the mononyms? Elvis, Marilyn, Madonna, Prince, they only need one name they’re so famous. Is there anyone who has become as ‘your-mum-knows-about-it’ (Hesz, 2017) famous in the past decade? The most likely candidate is Kim Kardashian, but her brand and fame predates the past decade, starting from the leaked sex tape in 2007. One commenter on The Economist’s Instagram post, posing the question, “Will anyone ever again be as famous as Marilyn and Elvis?” (Anon, 2022) notes that, “I think times have changed, long ago people perceived these icons as intangible, nowadays it’s as (sic) easy to become famous” (@_donnadakhakhni, 2022).

It certainly seems easier to achieve 15 minutes of fame now and these moments of fame are now distinguished by platform. We use phrases like “Instagram famous” or “YouTube famous” or “TikTok famous” to describe people, and sometimes they spill over into the mainstream like Justin Bieber (started on YouTube), but most of them don’t, yet are still famous to their millions of fans. For example, TikTok famous @AddisonRe has 88.7m followers worldwide and you’ve probably never heard of her. Forbes estimated that MrBeast of YouTube fame with 112 million subscribers earned $54m in 2021. Forbes even go as far as to say, “It’s only getting harder to distinguish a digital star from an Angelina (Jolie)”, (Brown and Freeman, 2022).

I’ve used people who some might call celebrities as working examples, however the trend applies to brand fame. Arguably the consequences are more acute for brands as people are interested in other people, especially entertaining ones, they’re not particularly interested in corporations. Here we can begin to see how achieving broad, mass fame is increasingly difficult and rare in a modern context.

IPA Databank findings tell us that aiming for fame will generate very large improvements in sales, market share, price sensitivity, loyalty, penetration, and profit (Binet and Field, 2013).

“The value of fame is twofold. It broadens the reach of the campaign (through sharing in various ways), and it creates a sense of popularity and advocacy for the brand (because people are talking about it)” (Binet and Field, 2019).

It is the ultimate north star for any brand-building campaign, combining the holy grail of broad reach, entertainment value and shareability. However, the explosion of broadcast channel availability and social media has meant that fame itself is increasingly fragmented. We’re facing an era of Fragmented Fame, shifting away from the type of mass, long term fame that the empirical evidence in the IPA Databank is based on.

Chasing increasingly elusive fame

Plainly, the changing nature of fame has been influenced by changes in the media landscape. Previously available rapid, mass reach is increasingly scarce.

Frazier in IPA’s Making Sense report highlights that, “Increasingly media planners are facing challenges when building broad-audience, high-reach campaigns and, with the exception of OOH, no single curated channel can reach 90%+ of All Adults per week, highlighting the need for nuanced understandings in media planning.” In addition, “Making Sense shows that brand building balance between digital and non-digital channels should be the absolute priority for brands that want to grow in the long term.” (Frazier, 2022).

There are two implications to unpack here:

- Commercial TV will continue to be one of the highest-reaching channels, however I believe that there will be fewer mass-reach shared moments that were the historic cornerstones of fame-building. Therefore, these scarcer moments will only be available to advertisers with deeper pockets.

- The increasing diversity of the media landscape and the powerful influence of media owner agendas have created a complex ecosystem that requires deeper knowledge, skills, tech and tools. This requires investment which, again, would be more readily available to advertisers with deeper pockets.

Broad, mass reach moments will soon become the preserve of the giants

Linear TV impacts have fallen 30% in the past 5 years meaning linear TV pricing inflation is at an historic high (Balvantrai, 2022). The TV market operates using a supply and demand mechanic so when eyeballs or ‘supply’ goes down, TV pricing goes up. ITV is launching ITVx to rival Netflix, Amazon Prime and Disney+ in an attempt to retain audiences and relevance. There will be a huge glut of content that can be streamed on demand that truly shared, mass viewing moments on the UK’s largest commercial broadcaster will be few and far between. What remains will be live sport, gameshow finals, and rare one-off specials like the Meghan and Harry interview with Oprah last year.

In more recent times, hundreds of D2C scale-up brands like Gousto and Peloton entered the TV advertising market creating a surge in demand for TV. Most of them have managed to grow beyond their scale-up status into big brand status as a result of TV investment therefore have since continued to increase TV investment “by double or triple digits over the last year” (Wiese, 2019).

This demand has applied even more pressure to an already price-inflating scenario.

Fewer opportunities to build broad reach on a reliable brand-building channel means price premiums are only affordable to brands with big budgets. Therefore, smaller brands are increasingly forced turn to other channels for effective reach.

Certainly, there are other AV channels such as BVOD, ad-funded subscription VOD like the new Netflix and Disney+ offerings, addressable TV, Social Media and YouTube which are more affordable. However, Ebiquity and Lumen have found that in terms of cost per attentive seconds, TV ROI still looks better than the highest-reaching alternatives of YouTube, Instagram and Facebook (Follett, 2021). TV still holds a dominant position when it comes to sure-fire brand building.

Therefore, outside of big brands with big budgets, those wanting to grow won’t be able to rely as heavily on TV and brand building will take more creativity, bravery, and patience than ever before.

A media headache

Despite audience needs remaining constant over the past 15 years (Frazier, 2022), methods of consumption have changed dramatically. Marketers and media planners need to grapple with, not just the proliferation of channels, but the increasing number of options available within channels and formats. In addition, combinations of channels will have different effects: the possible permutations become exponential and unwieldy to a marketer.

Therefore, improvement in knowledge and skills is necessary for clarity and effective communications planning. Tech and tools can and will be developed to facilitate deeper craft knowledge and skills. A change in perspective on the customer journey moving from a handful of touchpoints to a possible 10 or more is necessary to remain competitive. This unnerving increased complexity also means marketers need increased time investment to simplify and solve.

All of the above require time and resources which large brands will have more access to, meaning smaller brands are supressed again.

Being small but thinking mighty

Seemingly, size matters. These implications are a result of the “small size trap” an increasing phenomenon we are currently experiencing where large corporates are maintaining their leadership positions through innovation (Govindarajan et al., 2019). While, “if you are a small company this year, you are increasingly likely to remain a small company next year” (Govindarajan et al., 2019). This trend is corroborated with the findings that the size of a brand is the biggest determinant of advertising profitability (Dyson, 2014).

To make matters bleaker, many small brands have fallen into another trap. This one is more ROI focused and created through overreliance on digital performance channels. In recent history, SMEs are generally tasked with achieving a certain ROAS target for their advertising spend: highly efficient immediate growth. Tom Roach talks about these brands reaching a ‘performance plateau’, whereby the brand doesn’t seem to be attracting new customers and “all the low-hanging fruit seems to have been picked” so growth is stunted (Roach, 2022).

Even if the marketing team extricate themselves from this trap and start to invest in brand building more fervently, Dr. Kite’s experience is that it takes experimentation, and those who are dipping their toes into brand building for the first time don’t necessarily have the stomach for sustained experimentation: “four brand campaigns on TV were tried and found to have neither long-lived effects nor a positive return on investment. After evaluation, the advertiser understandably gave up and reallocated budget away from brand and into short-term sales activation online” (Kite, 2021).

As a small brand, chasing elusive mass fame sounds increasingly hopeless. However, keeping the small brands small will have negative consequences on our economy. We see it now where large brands pursue their own agenda, accountable to no one: the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal as a case in point.

In order to break through this ceiling, I believe that small brands need to consider how they achieve Fragmented Fame as mainstream fame is increasingly out of reach.

Fragmented Fame fuelled by recommendation media

Fragmentation sounds like a negative concept. However, it can be viewed as an opportunity with the right mindset, agility and talent: properties that a small brand is more likely to have compared to a larger brand (Hillenbrand, et al., 2019).

Social Media platforms would be a natural place to look to achieve Fragmented Fame given the reach it commands (75% of all adults) and the ease of sharing (Frazier, 2022). Social media platforms are quickly becoming less about seeing posts and videos from your friends but more about what the algorithm thinks you’ll like from other corners of the internet. Meta announced in July that the Facebook Home tab is where “we’ll recommend personalized content from creators and friends” (Zuckerberg, 2022), while a new Feeds tab is where you can see chronological posts from friends and groups you already follow. This was a key marker of the movement away from the ‘social’ in social media.

Social media has become recommendation media. It will supercharge Fragmented Fame and has been creating new community groups as people have been finding other likeminded folk they had not come across before. Recommendation media will require a shift in audience planning and thinking, a move away from broad brush demographics and thinking about communities based on interests, attitudes and tastes.

As people we are obviously multifaceted and can exist in several communities at once. It is therefore possible that recommendation algorithms will pave the way for Fragmented Fame to be transferred to an overlapping, adjacent community.

Fragmented Fame can also create passionate fandoms if the product and message truly resonates. Fans can be powerful vehicles for a small brand as they are customers+, they will purchase the product or service, but will also rave about a brand and defend it against the haters.

I am suggesting that small brands pursue Fragmented Fame to break out of the small size trap given the increasing barriers to entry to mass fame, while the opportunity can be multiplied by the rise of recommendation algorithms:

Current examples where Fragmented Fame has scaled a brand dramatically mainly exist in the world of entertainment. Given that recommendation media thrives on entertaining content and over a third of people in the UK use ad blockers (Anon. Statista, 2020), creativity and entertaining content are table stakes for a small brand seeking Fragmented Fame.

One example are FaZe Clan who are a professional esports and entertainment organisation that became a NASDAQ-listed company this year with a valuation of $550m, having started as three Call of Duty gamers on YouTube in 2010. They have conjured a brand using Fragmented Fame to break through the small-brand ceiling to become the most famous esports brand in the world.

Their recipe was relatively simple, they created video content they knew their audience would go mad for and strategically recruited more gamers who were also good on camera and brought their fandoms with them. They created a brand platform, notably requiring ‘FaZe’ to be added to the gamer’s tag e.g. FaZe Slasher, FaZe GuTLess, FaZe Fakie, FaZe Apex etc. They knew that gamers also had adjacent passions such as sneakers, streetwear, hip hop and basketball, so brought on creators to produce content to fulfil these avenues thus extending their influence and growing their scale. Next, they extended into fashion and lifestyle categories, with apparel collaborations with brands such as Champion, NFL and Manchester City FC. They now refer to themselves as a ‘global creative engine’ with a total reach of 510 million across social platforms (Anon, 2022).

As Zoe Scaman succinctly describes, “Rather than chasing after generic audiences, such as ‘all gamers’, or trying to create content that appeals to the broadest possible market, FaZe Clan pursue the opposite path, by focusing on the niches and creating for their interests… And they don’t worry about pigeonholes or limited reach, because they’re not looking at it in a piecemeal way, instead they can see what it adds up to - a sprawling FaZe Clan empire” (Scaman, 2021).

A less extreme example of tapping into Fragmented Fame for growth is Gucci’s behaviour recently. I appreciate that Gucci are not a small brand, however what they have done is recognise that Fragmented Fame is a pursuit that contributes something to their brand.

Gucci used TikTok famous Francis Bourgeois to front the drop of their latest The North Face collaboration. Bourgeois had become renowned for his eccentric and joyful trainspotting content on TikTok. At the time he only had two million followers, but Gucci made an unlikely bet on him and his appeal, on the platform and beyond.

Fragmented Fame principles

I appreciate that these two examples have creators, aka people, at the heart of them and they are not brands in the more traditional sense. However, I believe that there are principles small brands can borrow to create Fragmented Fame:

- Emotional (& entertaining) resonance

- Have a clear, distinctive truth

- Think of Zag breaking category norms

- Achieve creative consistency

- Build distinctive assets

- Aim for shareable reach

- Land and expand

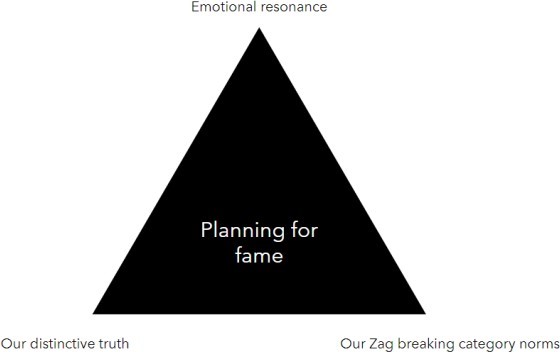

Using Bourgeois was out of character for Gucci as he is relatively niche for such a high-profile drop. However, it is likely a deliberate choice as they wanted to appeal to new audiences and achieve cut-through. In addition, the film got picked up by the mainstream press which extended the fame out of niche and into broad. Their approach managed to hit the ‘Planning for Fame’ notes created by Nick Kendall (see below).

I believe that small brands must consider these tenets seriously if they want to achieve Fragmented Fame. Specifically for Fragmented Fame, I would augment the model with entertainment value as a key consideration for ‘Emotional resonance’. The brand’s content will be competing with content from real people as well as competitor brand content as recommendation media is more likely to surface content that people enjoy and are entertained by.

Creating entertaining content was undoubtedly the supercharger for FaZe Clan’s growth and is extolled by Paul Feldwick. “I don’t accept the distinction between ‘content’ and ‘advertising’ – in my view much of the best advertising has been precisely ‘something created by/for a brand that people choose to consume” (Feldwick, 2021).

The three tenets of Emotional (and entertaining) resonance, a brand’s distinctive truth and zag-breaking category norms are vital not just for Fragmented Fame but to continue to build mental availability in the longer term. A small brand should also apply Sharp’s other brand growth principles of creative consistency and creating and reinforcing distinctive assets (Sharp, 2011).

These are important as aiming for Fragmented Fame among certain communities, whether they are united through attitude, interests and/or tastes, will require tailoring of content to give it the best chance of resonating. Therefore, the differing nature of the executions, will reinforce the need to maintain brand consistency and distinctiveness to secure recall and mitigate misattribution.

There is one rule I am re-interpreting for small brands with modest budgets: ‘reaching all buyers is vital, especially light, occasional buyers of the brand’ (Sharp, 2011). The Fragmented Frame approach will not always deliver on mass reach, but where budget is lacking, creativity can play a role. Fragmented Fame should rely heavily on the emotional and entertainment value of the brand’s content which should be tailored specifically for communities. It is predicated on recommendation media fuelling extended reach through community adjacencies and the content itself being shareable, hopefully spilling over into mass reaching channels.

A final principle is to land and expand. This can be applied in two ways:

- In the short term, where budget allows, to invest in additional channels

- In the longer term, remix the brand to appeal to adjacent communities

Studies find that media multiplier effects occur when more than one channel is used in communications, especially when they are synergistic e.g. Social Media and Online Video (Bell et al., 2021). Therefore if budgets allow, a small brand should always seek to deploy another channel or more to extend reach.

In the longer term, as FaZe Clan have evidenced, once a brand understands its audience it can show up in adjacent communities to achieve more Fragmented Fame and expand reach further. This is already tried and tested in the fashion and lifestyle category with, sometimes unlikely, collaborations – for instance, Primark x Greggs. If a small brand wants to break out of the small size trap then it is necessary to aim for Fragmented Fame across multiple community fragments.

Implications on a brand’s talent and functions

Creating Fragmented Fame will require both tangible and intangible changes for an organisation.

Starting with the tangible:

Constantly creating entertaining and emotionally resonant content for a community will require content creators to be embedded within a marketing team. They must truly understand what makes communities tick and be given the permission to act upon it. This may also require the brand to embrace a more decentralised workforce to maximise the value of creator talent but allow them to continue to thrive in their other job.

As a small brand, the product should be considered as a key touchpoint. It might need to be adapted for communities for emotional/entertaining resonance or, if expanding into adjacent communities, new products may have to be developed at pace. If not already, product teams should be part of the marketing function for the necessary agility and alignment of objectives.

It would be extremely lucky for Fragmentation Fame to happen overnight. A solid measurement framework will be essential to give reassurances to leadership that marketing efforts are making a difference, it will also serve to keep the marketing team honest and working towards the same objectives. Lastly, experimentation will be key when it comes to determining what content gets communities hooked and brand fame built. Therefore, having a framework in place to fairly assess results is crucial.

The intangible is more about mindset and company culture.

For a small brand that is likely to be under short term sales pressure, Fragmented Fame is quite an ask. It will require bravery and collective nerves of steel as it’s unlikely to happen overnight. Even if it did, small brands will only thrive through sustained Fragmented Fame which will also require commitment.

Creative bravery and nerves of steel are hard to ‘buy’ in as they’re more based on belief and hope. Arguably, a PR function’s activities and value are measured more in the medium to long term, therefore a PR team would be more accustomed to staying the course. For a small brand it would be advisable to incorporate PR specialists into the marketing team to give reassurances about longer term thinking.

Ultimately, small brands are at an advantage when aiming for Fragmented Fame, as they are not restricted by legacy structures, processes and ways of working like big brands.

Fame is within reach, just one fragment at a time.

This essay was submitted as part of the IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands. The 2026 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands is now open for applications.

View the full syllabus and submit your applicationThe opinions expressed here are those of the authors and were submitted in accordance with the IPA terms and conditions regarding the uploading and contribution of content to the IPA newsletters, IPA website, or other IPA media, and should not be interpreted as representing the opinion of the IPA.