Oliva Stubbings, Strategy Director at AMV BBDO earned a distinction for her 2017 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands 'I believe.' essay on harnessing the power of the 'Late Radicals'.

The consultant threat is very real. The trivialisation of our industry is an ongoing issue. The CMO is marginalised. But with advertising’s eye focussed on bringing in new young talent we are alienating the experts who can help the industry move up, and across the food chain. This essay presents a counter to the ageism that’s endemic in the industry and offers a new way to understand and extract the value that older people bring.

Introduction

Phyllida Barlow stands on the steps of the British Pavilion at Venice Biennale 2017. She wears a sensible Berghaus cagoul and a pair of Transitions Lenses. She has been selected to represent Great Britain in the highest profile contemporary art event in the world. She explains the title of her show Folly. The idea that something is foolhardy, risky and a play on the name of a building. Giant sculptural forms explode through doorways, the pavilion unable to contain them. She is 73 years old.

It’s 1981. Glenn Gould has returned to the piece of music that skyrocketed him to fam 26 years previously. He sits at the Steinway a little more hunched than he once did, bottle-top glasses obscure his eyes. After nearly an hour on stage critics around the world proclaim it to be his great ever performance. Aged 50 this is also the final performance.

To Palo Alto in 2007. Steve Jobs resplendent in Milk Tray Man polo neck stands on stage and pulls from his pocket the iPhone 1. He claims it will revolutionise the phone. For once he is being modest. It goes on to change the world. Aged 52 he is about to lead Apple into its next era of growth.

And a final stop in fictional Las Vegas in 1983. Robert De Niro as Sam ‘Ace’ Rothstein strides across a car park in a salmon coloured shirt and tie with a co-ordinating pink sports jacket. He gets into his Cadillac Eldorado Coupe, he turns the ignition and the car explores, throwing him across the screen and straight into the title sequence. The flames transition into the lights of the Las Vegas strip and the titles come up 'Martin Scorsese', 'Casino'. It’s a technique that will be imitated in the later James Bond films, but this time it was innovated by Saul and Elain Bass, who at 75 and 68 respectively were pioneering the latest computer graphics.

The thread that connects these four cases is that while in the final phases of their careers they are all creating game-changing art, music, technology, or graphic design. They are all innovating, risk-taking, playing, almost toying with the rules of their craft.

Imagine if music, art, science, law, finance, or any other creative or knowledge industry cut people off, kicking people out as they were hitting their stride. Yet that’s what we do in advertising.

Just 6% of people working in the industry are over 50.1 (according to the 2016 IPA Agency Census).

In this essay, I will question why advertising is the only creative industry that equates youth with creativity. I want to challenge the conceit that advertising is a young person’s game. This is a received wisdom based on short-sighted cost saving, and systematic and subconscious biases. All we have against the march of the management consultants is our creativity and culture, but managing a monoculture of under 30s causes the distortion of many practises that means we are taking our eye off the ball, and heightening the consultant threat.

If creativity is everything, I believe we must seek an all-ages approach as we currently push people out of the industry before they reach their most boundary-pushing, experimental Late Phase. We must unleash more over 50s on our clients and their briefs. I believe we could all benefit from rule breaking Late Phase Radicals.

Diversity is everywhere. Ageism is everywhere

Advertising is big on talking about diversity. Industry leaders have read the McKinsey study that demonstrates the increased business effects of a diverse workplace, have looked around to see few women in the C-suite or creative department, and a sea of white faces and acted. Agencies have created internal schemes that mentor women into management, have set up pledges to pay interns and creative placements a living wage, and have re-set the requirements for graduate schemes to attract a more diverse crowd.

To date, almost all diversity drives have focussed on gender and ethnicity. I believe age is the missing piece in the diversity puzzle. People who would balk at the thought of an all-male creative department, think nothing of a department with an age range of 25-35. Very little action is being taken.

A 2016 study by MEC and Campaign highlighted ageism as, 'Adland’s Next Frontier', yet the IPA/Campaign 2017 This Is Adland report deep-dives into gender and ethnicity with nothing on age. When the average age is 33.7, ageism is a distant issue for most people working in advertising. Turning 50 will happen in 20 years or so, and few positive roles or role models are put forward. The gist is that older people can move into an advisory position or mentor younger employees. This approach is consistent with the way growing older is represented in the West: as a period of reflection and the closing of opportunities where possibility is traded for experience.

Being grown-up is widely considered to be a matter of renouncing your hopes and dreams, accepting the limits of the reality you are given, resigning yourself to a life that will be less adventurous, worthwhile and significant than you supposed when you began it.

I will try to show that this doesn’t have to be the case. Across different creative industries and pursuits there are more positive roles, role models and work that offer a more optimistic take on the later stages of creative life, where creative practitioners achieve mastery, open up, and break the rules to create boundary pushing work.

But first I would like to diagnose how the youth cult comes about, and the problems it causes in the context of the advertising industry today. I will focus on the core creative and strategic disciplines as unique to our industry, but believe there is an applicability to the broader business.

Priming older people to underperform

As an industry, we worship at the altar of youth.

Young people are essential for the future of the industry – they’ll be staffing it, and of course, they are good at it. We only need to consult the credits of 2016 IPA Effectiveness or Cannes Lions Gold Winners to see that. Thankfully it has always been an industry where age-grading could be disrupted by creative or strategic brilliance, where talent speaks louder than title. But I believe the pendulum has swung too far.

For the last 10 years, the industry has made great efforts to attract young talent who once eagerly filed into grad schemes and creative placements but are now joining tech companies or in-house creative teams of a new breed of client organisations. To show young people the industry is still eager for them to join, agencies have created a system of awards, plaudits and company cultures that alienates anyone with kids at home, and is downright hostile to anyone over 50. From 30 under 30 awards, to Young Lions, and booze-fuelled team bonding away-holidays, the industry sends older employees very public signals that they are not welcome. For other knowledge industries – medicine, law, finance, around 30% of the workforce are 50+. In advertising it is only 6%.

Where do the missing 24% go?

There are two routes out – the visible move on to “better” things – directing commercials, a highly-paid client role, writing films, TV and novels; or silently slipping away into underemployment. Speaking to Executive Creative Directors some themes emerged about why older creatives don’t perform. Stories of cynicism in the place of enthusiasm, aggression in the face of jealousy, inflated egos and salaries, or belligerent luddites that won’t move with the times. It is not difficult to see why this cohort might be underemployed.

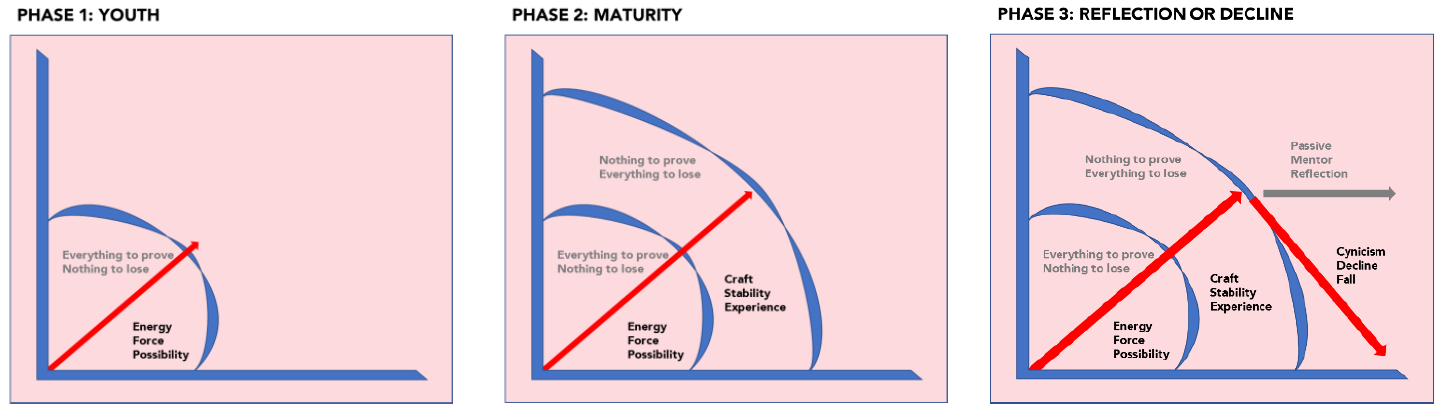

Mapping the attitude to employees shows a depressing final trajectory.

However, I believe many older people find themselves in a social-psychological predicament that arises when confronted with widely-known negative stereotypes about one’s group. In multiple studies Steele and Aronson found that when African American students were primed with negative stereotypes about the academic underachievement of their race they performed worse in standardised tests. They had internalised the narrative and it was affecting their performance. The plaudits and the language around young people in the advertising industry, and the absence of older people has a similar effect. The youth cult primes older employees to underperform.

So, against the myth of the digital native, the counter-myth of the slow, old team takes hold. These narratives percolate inside and riddle older employees with self-doubt. The myths become useful for anyone looking to cut some costs as procurement’s scythe sweeps across the industry. Cheaper? Yes, but faster, better? I’m not so sure.

Ethics aside, and beyond the broad benefits of diversity that have been covered at length elsewhere, older people will have an essential role to play in tomorrow’s industry.

- In the 2017 IPA report on the Future of Agencies there are three relevant themes:

going up the food chain - sense-makers of complex technologies

- the added value of strategic thinking

Yet the youth cult blocks our ability to deliver against them.

The youth cult distorts business practices

The core of our business

So many of the new problems we face are the same as the old ones – only in a new guise.

For younger people, this may be the first time they are tackling these briefs. But older practitioners have the experience and muscle memory to spot commonalities and apply lessons from the past to the current situation. Without them we get stuck in Groundhog Day.

The result? The industry answers these problems with inexperience, using shiny new innovations, not-to-be-missed opportunities, must-be-jumped-on bandwagons. These innovations eventually emerge as a false dawn. By failing to learn from experience, we are continually setting ourselves up to fail.

While adland’s memory doesn’t stretch back that far, the average age of FTSE 100 boards steadily rise. The average age of non-executive directors sits at 59.6 while executive directors are 52.8. Advertising is looking increasingly inexperienced.

Empirical evidence shows that many board members already view advertising as trivial. We perpetuate this by trumpeting and trivialising every new initiative as a revolution. This undermines our credibility with the board, the gatekeepers of the gestalt brand.

Struggle to extend up the food chain

As the credibility gap grows between agency and senior clients, management consultants creep in. While advertising grows at 3% y-o-y, management consultancy has grown by nearly 10% every year since 2013. Not only has the industry grown in absolute terms, but the firms have expanded their remit, encroaching on the core brand business by developing creative capabilities and acquiring creative agencies, and blocking the growth of non-consultancy-owned agencies into new revenue pools. They have done this by flexing the connections they have with the CIO, or CFO – board members more influential than the CMO to turn digital transformation projects into digital marketing projects.

The creative agency’s route into future growth lies in its ability to go up, and across the food chain. However, agencies are currently not sending the right signals. The fifty-something C-Suite are subject to the same biases as the rest of us and even with facts, the first impressions of youth are hard to shake off. Agencies struggle to field the level of expertise required.

In the battle for share of marketing (and talent) agencies have culture and creativity, but the youth cult puts both at risk.

Expertise by the book

Over the last 10 years there has been a growing and invaluable body of evidence of how advertising works, from understanding how people tend not to make decisions but are nudged towards them, how advertising is a low involvement media, or to the rules of markets and share.

In the hands of experts, the laws of marketing become liberating, but in the hands of the inexperienced, they are laws that demand the user err on the side of conservatism.

Take three examples from Byron Sharp:

- The 'balance sheet' demands calling out the brand early in the advertising.

- Continuously reach all buyers of the category reduced to - don’t alienate anyone with this creative work, must appeal to everyone.

- Physical and mental availability reduced to the need to buy reach and distribution rather than the size of the brand in the mind.

We have replaced earned expertise with Googling, where we find how-to guides to creating advertising, with rules on when to introduce the brand, how to grab attention in the first 5 seconds. The net of this is a formulaic approach, and a content deluge that goes unwatched. The youth cult needs to learn the rules, and have the experience to bend them to serve their interests.

Short-term careers, culture and campaigns

Short-term careers

Modern labour is increasingly short-term in character, as short term jobs replace long-term careers within a single institution.

If the modern workplace is one that has transitioned from long to short term, there is nowhere that represents that transition better than the advertising industry. While nationally, annual employee turnover sits at 10%, in advertising it sits at 30%. Half of all employees stay for 2 years or less. Younger employees are 5 times more likely to change jobs than older talent.

There are clearly financial implications of the short-term careers of the youth cult. To replace employees earning £25k+ the logistics, through recruitment agency fees etc., costs £5k. A far greater proportion of costs to employers comes from lost productivity, as new employees come up to speed, accounting for £21k. An agency with 100 employees and a churn of junior staff of 39.3%, the true cost of £26, 000 per employee gets to a figure of over a £1 million per year.

Culture is the intangible price of staff turnover

An organically fostered company culture is more likely to fuel collaboration and cross-pollination of ideas, whereas a 'culture' dictated top-down by management is more likely to breed discontentment.

It is here that the intangible price of staff turnover is seen. With a constantly shifting set of people, agency culture becomes ephemeral, psychological safety is difficult to achieve. Agencies become near Ships of Theseus where whole departments might have churned within a few years.

Short Term Careers Cost Creative Payback

A short-term focus undermines the case for creativity

The blame for short-termism in advertising is usually planted at the door of the client organisation. Quarterly reporting demands results in quarter. More creative brand campaigns that only pay back over the long term are sacrificed for the short term. CMOs are the highest turnover members of the C-Suite, with 40% having been in the role for less than two years, the time it takes for highly creative campaigns to pay back. Unattached and eager to visibly impact, they will throw out a campaign that shows any sign of underperformance. When the creative agency is also staffed by people who have a limited history on the account, they too are less willing to protect the campaign.

An industry stuck in perpetual adolescene

In advertising, young people are synonymous with new ideas, fresh ways of looking at things. They are expected to have a better grip on technology and innovation and they are expected to want to spark a change. Launching yet another award for young creatives the ECD of AKQA says, "Youth risks experimentation. With no laurels to rest on, it has no fear of undoing previous successes […] without the immediate requirement to satisfy risk-averse middle management, always take a leap of faith".

In 1971 Stephen King worried about our industry’s ability to go upstream yet we rely on an inexperienced work force. In 1985 Peter Drucker pointed out the pressure to deliver in the short term yet we invest in a high turnover workforce.

New entrants have come into the industry, declaring the digital, content, AI, or programmatic revolution but end up dividing the share of the advertising market into smaller pieces. We are all left fighting over increasingly inconsequential scraps. As an industry we end up chasing costs down rather than looking upwards to future revenues.

The business model demands we work long hours, for low costs so we rely on young people. We say the young have fresh ideas, are cool, experimental, willing to take leaps of faith, because it drives a profit. But I don’t believe innovation or creative rule-breaking is the exclusive domain of youth, and I think that using older talent to do the same can drive greater future revenue.

This inevitably means putting our people front and centre – and selling their expertise in the project room, as well as the advertising product created as an output. Empirical evidence shows how disenfranchised the CMO has become from the rest of the board. If we are to properly support them I don’t think we can rely on inexpensive junior talent.

I’m going to look at examples from broader industries to see how older practitioners add value. Then I will cover how advertising can organise to harness the value of people in the Late Phase.

Late phase creativity

The Tate Britain’s recent exhibition of JMW Turner’s late works, Painting Set Free, starts in 1835 when Turner has just turned 60. In the early 19th Century people thought by 60, you were 'on the edge of senility and starting to lose it' – a bit like being 50+ in advertising in the early 21th Century. Despite the traditional subject matter the paintings are abstract and ahead of their time. Closely inspecting the canvas, the curator remarks, 'he has a supreme confidence in the handling of his paint.'

Across the creative industries there are positive models for later life creativity where older people’s role is not reduced to passive mentorship, but an expert, or originator. At the beginning of the essay I touched on Phyllida Barlow, Glenn Gould, Steve Jobs, & Saul Bass. There are countless cases be it from business in Jeff Bezos, or Ratan Tata; in art, from Hockney, to JMW Turner and Louise Bourgeois; and music, in Beethoven, John Lee Hooker, or David Bowie.

There is a remarkable similarity in the criticism of the Late Phase of artists, musicians, and writers. It is a similarity that crosses generations and genders that their late works display specific features that are distinct from earlier works. They challenge the aesthetic of the contemporaries, and point towards the aesthetic of a next generation in their discipline.

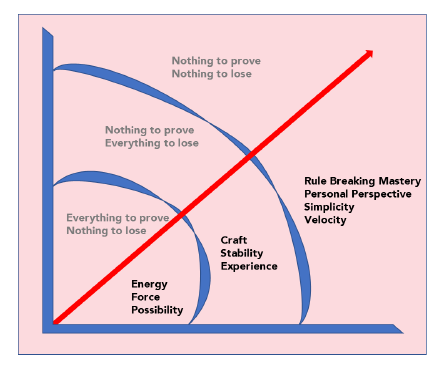

There are four distinct themes that emerge, demonstrating the value added in the Late Phase that advertising currently misses out on as people are cut off, either moved away from practitioner into mentor role, or leave the industry. Understanding what these successful practitioners do can point towards how advertising can reap the rewards of The Late Phase.

Four defining features of the late phase

Mastery is a license to break the rules

The Late Phase breaks the rules. Having spent the best part of 40 years practising and refining their craft within the bounds of whatever category they work in, they are given the license by the public or their patron to do whatever the hell they want, and declare it exceptional. No longer encumbered by what people think, or what is the “right” thing to do, they are set free.

Exhibit A: David Hockney, A Bigger Exhibition, 2013: The iPad becomes a tool for high art.

Artists have been making digital art since the early 80s but none of them achieved the level of press, and recognition that Hockney did. Since the 1960s Hockney has been at the leading edge of contemporary art. His intimate knowledge of past masters, coupled with expertise over forty years gives him the license to be respected and reinvent painting as a digital art form.

Therefore: The current thinking in advertising demands, the way we do things round here, are broken by the young, unencumbered by years on the frontline. At times they unwittingly break the wrong rules… The Late Phase offers an attack from another front, one that carries the weight of experience.

Guided by self

The Late Phase is inner directed and does not need the approval of others. Guided by a sense of Torschlusspanik, the fear that time is running out to act and doors are closing. There is a new urgency driving personal projects.

Exhibit B: David Bowie, Blackstar

Many rock stars spend their last years touring their greatest hits for the pleasure of others. “Bowie has put many of his selves to rest over the last half-century, only to rise again with a different guise” in his most poignant and personal work.

Therefore: Commercial creativity is in its nature creative for someone or something else. However, it is an industry bent on the creation of orthodoxies, from weepy storytelling, to save-the-world purpose. A more personal voice can break those orthodoxies.

Prizing universal simplicity

Complex solutions make us feel smart but the Late Phase Creative has nothing to prove. While the young feel sophisticated discussing the obtuse and abstract. The Late Phase doesn’t need to prove how smart they are with complicated processes and can instead connect universally.

Exhibit C: Matisse Papercuts, a return to a universal

There are multiple theories as to what spurs a creative on to create such radicalism so late in life. For Matisse, it was an ailment that meant he could not stand to paint, and instead used scissors and paper, creating universal shapes, and colours.

Therefore: When faced with marketing complexity the Late Phase can make sense, and make universal, stripping back to the essentials. Increasingly time-starved senior clients prize clarity and brevity above all else.

High-velocity thinking to run efficiently

The Late Phase works at high velocity. Making decisions at pace requires an adaptive unconscious, the power to think without thinking, built up from experiences and case histories.

Exhibit D: Jeff Bezos, 52, writes in his 2016 shareholder letter that the way to keep a business running with the dynamism of Day 1 is 'to somehow make high-quality, high-velocity decisions […] you need to be good at quickly recognising and correcting bad decisions.'

Therefore: The current agency model demands inexpensive youth working a large quantity of hours for a low rate. The Late Phase can solve twice the problems in half the time.

Constructing the Late Radical

13-19 year olds have always existed but it wasn’t until they were termed Teenagers in the 1950s that a culture and economy could be built around them. The naming of a thing creates a social construct with associations and ideas that frames how we perceive them. In today’s industry summoning “The Creatives” into a client meeting signals meaning and sets expectations. To harness the power of the older cohort we need a positive frame for this group. To communicate their expertise and innovation they will be known as the Late Radicals.

The Late Radicals are:

- Masters in their trade, looking forwards for new possibilities with the credit to exploit them.

- Driven by self, caring less about what others think, but with enough experience to achieve universality

- An ability to cut through and break complicated tasks down in the simplest terms.

- Working at high velocity – with years of experience baked into an adaptive unconscious.

The career trajectory that extends to the Late Radical

Harnessing the power of the Late Radical

To meet new client demands and take advantage of late stage creativity we need to break our business model of long hours and cheap labour. This will mean changing the structure and culture of our industry from how we service accounts, to how we employ and remunerate staff. In Section One I outlined how the older employee leaves the industry either voluntarily, moving on to better things, or faces underemployment through underperformance. In this section I will outline how to mitigate against both forces. This will be a long-term project and needs to be tackled in two directions to ensure the best talent stays in the industry.

First, we must create new norms and reframe the way colleagues and clients view the Late Radicals and then we must break the business model to make the industry more attractive to them.

Initiatives to improve others' view of Late Radicals: Mitigating against negative group stereotypes

Employers often equate experience with inflexibility, technophobia, and unrealistic pay expectations. In the immediate term we need to break those myths with initiatives to prime clients, employers, and colleagues to welcome older employees.

1.) Rethinking remuneration

There is an expectation that as you progress in experience your salary grows. With great salary comes great responsibility – often not wanted. In addition, middle-aged employees with children at home, versus older employees with fewer dependents have different remuneration requirements. The Late Radical will have more flexible remuneration options with options for Bell Curve lifetime salaries, or pay based on value created.

2.) Create awards and plaudits that publicly recognise their contribution

Creative awards shows in 2017 are more about agency publicity than celebrating high performing work. This plays perfectly to the Late Radical agenda. Just as the industry creates awards to attract young talent so we must create public symbols of Late Phase Radicalism. At Cannes we will create the Late Radical Lion that celebrates ground breaking creative that produced transformational business effect, open to 50+ talent from any discipline.

3.) Create a contingency workforce of 50+ Late Radicals

Outside of advertising there are different models that drive diversity. In fashion, specialist modelling agencies like Anti-Agency or Ugly, provide a broader church. In tech, many start-ups have an older non-exec director to take into VC meetings. We will build a freelance of network of Late Radicals, marketed as high velocity thinkers, available to hire by the hour, day or project.

Initiatives to encourage more Late Radicals: Mitigating against the move to 'better things'

The advertising industry is hostile to older workers with long hours, and lower pay than other knowledge industries. Many older employees have experience but no longer wish to have the stress of managerial responsibilities. There are groups of older workers who have retired on adequate pensions but still seek interesting employment. To retain or regain the Late Radical we must break elements of our business model. When reinventing a business model the first step is to, 'realize that success starts by not thinking about business models at all. It starts with thinking about the opportunity to satisfy a real customer who needs a job done.'

As we adapt we need to change the Customer Value Proposition – from selling services to experiences. To do that we need to look at our key resource, moving from high hours of energetic youth to concentrated hours of true experts that can support CMO and communicate with other key board members.

There are four initiatives that would make this possible:

1.) The Late Radicals are project employees that solve the big problems

There will be no more career “slumming” where expert resources are wasted on tasks that deliver no value to the agency or gratification for the employee. The Late Radical will not be required for the prosaic day-to-day but will be brought in to solve the big problems, and set the path, completing annual planning, & new brand campaigns.

2.) The Late Radicals earn as they create value

The long hours are oft-cited as the reason we leak talent, when experts with families are no longer willing to give weekend time to employers for no additional fee. The current remuneration model rewards hard-working employees with an annual bonus, while behavioural economics principles tell us that we place a higher value on immediate reward than a reward in the long term. The Late Radical will be remunerated for extra value created and will be remunerated at point of completion.

3.) The Late Radicals are promoted out of management

Experienced staff are currently promoted into management and away from practitioner level. With management comes distractions with energy spent on HR and personnel issues rather than the creation of value for brands. The Late Radical’s attention will be solely focused on driving value for brand and agency. The Late Radical will fall in love with the craft all over again.

4.) The Late Radicals need Lazarus figures to bring them back

The current Mentor/Mentee model demands the older Mentor passively advises the young acolyte. The Late Radical will not be a passive player but a practitioner. By the mid-eighties, Saul and Elaine Bass were living in upstate New York, working on personal projects in relative obscurity. Martin Scorsese could not get the title sequence right for Goodfellas. Someone suggested Saul Bass, and although Scorsese was initially intimidated, he invited him to develop the project. It was the beginning of a four-film relationship. 30 and 40-something Creative and Strategy Directors working today must brief out difficult projects to personal advertising heroes, many of whom were flushed out of the industry in the first wave of digital disruption.

Conclusion

The consultant threat is very real. The trivialisation of our industry is an ongoing issue. The CMO is marginalised and struggling for relevance. But with the industry’s eye solely focussed on bringing in new young talent, there are not enough implicit signals being sent to the experienced. Unlike the youth issue, this is not a problem that can be solved with bean bag chairs and Friday beers, but with disruption to our business model.

Predicting the future is something of a fool’s game. What we can be sure of is, like death and taxes, we’re all getting older - as an ageing society, and more personally, as an individual.

I believe the Late Radical offers a more optimistic view of the career path that might await the young talent we are so focused on.

Olivia Stubbings is a Strategy Director at AMV BBDO. This essay earned her a distinction on the IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands. The 2026 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands is now open for applications.

View the full syllabus and submit your applicationThe opinions expressed here are those of the authors and were submitted in accordance with the IPA terms and conditions regarding the uploading and contribution of content to the IPA newsletters, IPA website, or other IPA media, and should not be interpreted as representing the opinion of the IPA.