Gareth Price was awarded the President’s Prize on the 2016/17 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands for this essay on combatting short-termism.

I’m not sure what the right answer is but I believe the world is too short-term focused. All the things I’ve seen in the 10 years since I’ve joined Allianz have been shorter, shorter, shorter.

While the danger of short-termism to brands isn’t new, the evidence suggests it’s gathering pace. A 2017 report by McKinsey Global Institute discovered that two-thirds of executives believe short-term pressures have further accelerated since 2012.

The principal cause is investors seeking quicker returns, with the average holding time for shares on the world’s largest stock exchange falling from eight years in 1960 to less than eight months today.

Boardrooms are equally culpable in their response: 80% of CFOs at 400 of the world’s largest companies would sacrifice a firm’s economic value to meet this quarter’s earnings expectations.

And with CMO tenures the shortest of all executives, it’s not surprising marketers face growing pressure to deliver instant results. Indeed, a recent IPA study discovered that the proportion of advertising campaigns that ran for less than six months more than quadrupled between 2006 and 2014.

Boardrooms clearly see enormous value in brands. All too often, however, an excessive focus on achieving immediate returns undermines their ability to deliver long-term profit growth; merely serving to increase price sensitivity or shrink the number of prospective buyers the brand communicates with.

As an industry, I believe we need to change tack in three respects. Firstly, we must stop railing against the short-termism of investors and recognise it can be a sensible strategy at the individual level.

Secondly, as proponents of behavioural economics would highlight, we can’t hope to tackle the issue by changing attitudes, these will follow behavioural change.

Finally, we should look at our own complicity. The pursuit of more cost-efficient reach, rather than where is most effective; our infatuation with what new technologies make possible, rather than with what works; and the preoccupation with achieving an immediate ROI, rather than a larger profit in the long-term, not only risks undermining the effectiveness of our campaigns and their ability to build brands, but has arguably manifested in the biggest threat to the advertising industry to date: the rampant adoption of ad-blocking.

Short-termism is a problem that must first be confronted at the executive level to ensure marketers are in a position to make decisions that prioritise effectiveness over efficiency. This requires us to pursue the more ambitious goal of encouraging investors to hold shares for longer. Above all else, this will ensure boards invest in long-term strategies.

I believe the solution is to launch an organisation backed by a consortium of marketing bodies in partnership with the Investment Association.

Thinklong’s primary ambition is to create an environment in which brands can flourish by tackling the source of the short-term pressures they face.

The secondary one, while unashamedly self-interested, is something I believe is integral to future profitability: increasing brand communications budgets by positioning the industry as the harbinger of long-term growth.

While the former requires us to change the behaviour of investors and executives, the latter compels us to scrutinise our own actions.

Although this essay calls for collective action - which I believe is necessary to combat the dwindling length of shareholding and the failure to view marketing communications as a capital investment - individual companies can still implement the measures proposed to gain a competitive advantage.

In that respect, Thinklong is as much about inspiring a movement to embrace long-term thinking, as it is about providing a framework to achieve it.

Stop criticising investors and focus on behavioural change

If everyone in society was to borrow too much at once, the effect on the economy would be disastrous. Conversely, if we all stopped borrowing, a deep recession would ensue3.

What works at the individual level, frequently doesn’t at the aggregate.

We would be wise to reflect on this when examining the role of the brand in creating long-term value.

While short-termism is damaging to companies, for the individual investor, it can be a sensible strategy. Faced with future uncertainty, demanding reduced capital spending and seeking an immediate return is hardly irrational.

Educating investors on the dangers of short-termism has always achieved little. As John Maynard Keynes famously stated, ‘investment based on genuine long-term expectation is so difficult today as to be scarcely practicable’.

While few would disagree that companies should aim to deliver profit growth in the long-term, short-termism persists amongst investors, executives, and marketers alike.

Besides offering a potentially lucrative approach to investing, our brains are hard-wired for instant gratification through dopamine released by immediate gains. Long-termism doesn’t come naturally to any of us.

As behavioural economists would testify, change the behaviour and attitudes will follow.

Profit growth requires investment

To understand the impact of short-termism on brands and marketing communications, we must first explore the role both play in delivering a profit.

The primary goal of a company is to maximise shareholder value by returning cash to investors in the form of a dividend, stock repurchase, and/or increase in share price.

This requires the business to make a profit now and/or convince the market this will happen in future.

Besides acquiring and divesting assets, profit is principally achieved by increasing revenue or reducing costs. The latter is the quickest way to accomplish this, but offers finite potential - costs can only be cut to a certain point - and fails to demonstrate to the market where future growth will come from.

Section 172 of the Companies Act 2006 states that all boards have a ‘duty to promote the success of the company, [including] the likely consequences of any decision in the long-term’.

Repeatedly cutting costs is not a sustainable strategy.

To increase revenue, a company must sell more goods or sell those goods for more. While the former may seem like a more intuitive way of achieving this, at a profit margin of 20%, maintaining sales following a price increase of 1% delivers five times more profit than a 1% rise in volume.

For this reason, marketing communications designed to reduce price sensitivity is frequently more profitable than activity which aims to drive sales.

To maintain profit growth, a company must therefore create and develop an asset that enables them to charge a higher price than competitors selling functionally similar goods or services.

The value of the brand

Brands are a product of their history, generating rents for a company based on the reputation and equity they have built over the years.

Strong brands extend and enhance what the company is offering. They also create value for shareholders by increasing cash flows and reducing the cost of capital (Doyle, 2000).

A study by Citibank found that companies with well-known brands outperform the market by between 15 and 20% over a 15-year period.

Using salary data from nearly 3,000 executives, researchers found that companies with strong brands pay them less than other firms. Given salaries account for up to 50% of operating expenses, brands save companies considerable sums too.

A strong brand also enables a business to maintain that price premium so critical to profit by creating intangible differences between products and services that offer little tangible difference to competitor offerings.

How short-termism inhibits brand growth

The days of the City undervaluing brands has long been over. The fact that in 2015, a company was willing to pay a multiple of 35 times price over earnings for a newspaper - when print media has long been deemed a dying business - is a testament to the enduring power of the brand.

Taking their lead from investors, it’s simply not the case boardrooms don’t value brands either.

However, aggressive quarterly earnings targets, reduced trading times, the rise of the institutional investor, and increased market volatility have all played a role in the excessive focus on short-term results at the expense of long-term interests.

Brands remain one of the most valuable assets in business and yet, not only are companies failing to invest in them, they are increasingly making decisions that erode their value.

In a recent letter to S&P 500 CEOs, BlackRock’s Larry Fink bemoaned ‘today’s culture of quarterly earnings hysteria [that’s] totally contrary to the long-term approach we need’.

A company struggling to hit quarterly targets encourages managers to:

- focus communications on driving sales volumes;

- compete on price; and/or

- cut marketing costs.

Focusing communications on driving sales volumes

By activating existing customers and in-market prospects, rational messaging can deliver an immediate sales response by providing practical information. If an individual is not looking to buy at that moment, however, it will be irrelevant and unlikely to create a memory.

Robert Heath describes how a combination of perceptual filtering, counter-argument, and general lethargy means that most ads ‘fail to register rational messages for longer than a few seconds after the ad has finished’.

Emotions create much stronger memories by providing a lift which enables us to mark things as good, bad, or indifferent (Damasio, 1994. Providing information can achieve this effect, but it would have to provoke an automatic emotional response.

An exhortation to buy is unlikely to do so, particularly amongst the broader audience not presently considering purchasing. Effective communication creates a positive impression of the brand amongst that wider audience, subtly influencing their later behaviour.

By building and strengthening relevant memory structures, it increases the likelihood the brand will come to mind in more buying situations and on more usage occasions.

This not only helps the brand sell more, more often, but makes it more resilient to competitive pricing, enabling the business to deliver future cash flows at higher margins.

As Binet and Field (2013) demonstrate, campaigns that perform well on long-term metrics like profit and market share don’t do as well at achieving an immediate response.

Focusing too much expenditure on communication designed to boost immediate sales volumes therefore damages a brand’s ability to deliver a greater profit in future.

Competing on price

Promotional tactics can boost revenue by attracting people in buying mode.

However, a large-scale study of price-cutting promotions discovered there are no positive after-effects: sales volumes simply revert to the same level as before, with “virtually no new buyers” (Ehrenberg et al, 1994).

Nearly everyone buying during a promotion has bought the brand at some stage in the past. It does nothing to alter their ongoing purchase propensity either, simply bringing a future sale forward at a reduced margin.

Discounting also teaches customers the brand isn’t worth the price normally paid. This implicitly communicates the company is desperate for sales and the brand has lost momentum.

As Jeremy Bullmore highlights, ‘[a] low price can simultaneously lower the barrier to entry and increase suspicions about quality’.

P&G’s CFO Jon Moeller describes growing a business by reducing prices as ‘a pyrrhic victory’.

To achieve profit growth tomorrow, a brand must not undermine its price premium today.

Cutting marketing costs

The Canadian Association of Marketing Professionals recently stated that ‘ROI is the most important metric’ and it continues to top surveys of marketers’ measurement priorities.

However, the quickest way to increase ROI is to cut costs, triggering a downward cycle that further reduces the number of prospective buyers the brand communicates with.

The largest payback comes from communicating with light and potential future buyers who know and think less about the brand.

Given purchase frequency reflects market share and category norms, focusing on acquisition is the optimal way to achieve growth (Sharp, 2010).

Extracting more and more value from a shrinking pool of customers will always lose out to obtaining a little more value from a larger number of people in the long run.

A failure to preserve mental availability across all potential category buyers erodes the value of the brand. This is evident in the fact brands which maintain or increase advertising spend during a recession experience double the growth in share compared with those who reduce investment.

Even simply to maintain their current market share, brands can never stop investing in communications.

The need for collective action

Despite all the evidence for how brands deliver profit growth in the long-term, companies are increasingly sacrificing larger future gains for smaller, more immediate returns.

I don’t believe this is the fault of marketers. Nor is it the fault of management. Neither should we continue blaming investors.

It would be difficult to find anyone that thinks a company should disregard long-term objectives, so the first requirement must be to nudge investors into holding shares for longer.

This will release executives and marketers from the need to focus on prioritising short-term returns.

I believe a consortium of marketing bodies - with backing from the IA - can help achieve this.

In addition to providing credibility to the project within the investment community, the two have a shared agenda, with the IA recently launching a ‘Productivity Action Plan’ to ‘catalyse the provision of long-term finance’.

Thinklong’s ambition is to encourage long-term investment with the secondary goal of growing brand communications expenditure. I, therefore, propose a seven-point manifesto to support these aims.

The intention being to shape both investor behaviour and executives’ perception of brand communications, as well as provide a framework for companies to create long-term profit growth.

1. Lobby for practices that encourage long-term investment

Professor Kay’s government review concluded that the quality, rather than the amount, of engagement by shareholders, determines whether the influence of equity markets on corporate decisions is beneficial or damaging to the long-term interests of companies.

At present, markets “encourage exit (the sale of shares) over voice (the exchange of views with the company) as a means of engagement, replacing the concerned investor with the anonymous trader”.

In France, under the Florange Act, investors who have owned shares in a company for more than two years are automatically entitled to double voting rights11. This provides greater stability to boards to set company strategy prioritising long-term interests.

Similarly, encouraging active ownership by limiting the practice of proxy voting would result in institutional investors - who account for two-thirds of equity in publicly listed companies - holding shares longer.

Increasing transaction costs would further reduce day trading, dampening short-term volatility. Subrahmanyam (1998) suggests transaction taxes ‘reduce short-termism in information acquisition by increasing traders’ incentives to acquire fundamental information, thereby enhancing long-term discovery’.

These measures should form part of a sustained lobbying plan that would indirectly support increased investment in activities that focus on delivering continued profit growth.

Equally importantly, it underlines the extent of the brand communications industry’s ambition to lead on this issue, positioning it as the champion of long-term thinking.

2. Enhance company reporting by detailing future marketing expenditure

Companies may fear that detailing future marketing expenditure at the brand-level provides competitors with too much information, but it represents a powerful signal the company is invested in the long-term.

A Harvard Business School analysis of 70,000 earnings calls found that companies using words and phrases suggesting a short-term emphasis had ‘higher absolute discretionary accruals, were apt to have very small positive earnings and barely beat analyst forecasts’. Their cost of capital was also 0.42% higher than average.

The language used in company reports primes the market: a short-term orientation attracts like-minded investors.

The predominance of short-termism in the financial markets means the potential rewards from long-term investing are underexploited.

Detailing future spend, and highlighting it more prominently in presentations to institutional investors, emphasises the company plans to deliver long-term profit growth, attracting the attention of investors with long-term horizons.

Thinklong should encourage executives to adopt this approach by highlighting the benefits it brings.

Indeed, the Kay review recommends ‘communicat[ing] information to shareholders which aids understanding of the future prospects of the company, even if this means going beyond the strict requirements of accounting standards’.

Like Ulysses tying himself to a mast to resist the call of the sirens, a public commitment to investment will ensure marketers face less pressure to cut costs to hit quarterly targets.

3. Link long-term strategy to brand valuation

The IA reports that portfolio managers believe companies provide too little meaningful information concerning future expenditure and how it will improve the business.

A review of 100 annual reports found just nine made a clear link between strategy and KPIs. Too often, planning was merely an exercise in ‘spreadsheet manipulation’.

The economic-use approach to brand valuation is based on the discounted cash flow of future earnings and the strength of the brand. It requires a diagnostic analysis of where and how the business can generate future profit.

By connecting brand drivers to a valuation model, Joanna Seddon says it can ‘serve as a tool to identify strategies most likely to increase’.

Seddon suggests it can help management understand:

- what makes the brand valuable;

- how it has an impact on the business; and

- what justifies investing in it.

Linking current marketing decisions to future performance ensures the long-term impact of brand campaigns is weighted against short-term activations.

A transparent brand valuation process can help to reveal where the largest gains can be made from future investments, ensuring planning becomes more rigorous and strategy is linked to KPIs.

Rather than using it to create ranking tables of questionable worth, its value lies in determining a course of action to maximise brand growth, and demonstrating those plans to CFOs and investors in a language they understand.

As Seddon highlights, this puts brand decisions on ‘a different, more robust footing’. The establishment of ISO 10668 firmly opens marketing’s door to the boardroom in that respect.

Tracking the rise in value delivered by the brand further ensures boardrooms are less addicted to immediate metrics, resulting in marketing plans that aren't dictated by quarterly cycles.

David Haigh, for example, reports that an international cigarette company monitored the growth and decline of brand value in regular management reports.

Research by an investment bank also discovered that advertising’s capacity to boost Orange’s share value equated to an increased market capitalisation of £3 billion on a budget of just £44 million.

It remains a neglected way of credibly demonstrating the value of long-term brand communications in creating shareholder value, however.

Collaborating with brand valuation firms and investment banks for this type of evaluation will more robustly highlight its role in achieving financial success, helping to justify future expenditure, and put the focus on longer-term strategy.

4. Remove measures that don’t relate to long-term value creation

The rise of zero-based budgeting and performance-based agency remuneration attest to the importance of measuring the impact of marketing.

But if the only way to demonstrate its value back to the business is through the immediate sales achieved, it will inevitably push marketers towards doing more short-term activations that harm the brand in the long-run.

As the government’s review into equity markets highlights, no single metric or model can provide a sure guide to long-term value in companies.

However, reducing noise in information and removing measures that don’t relate to long-term value creation are important first steps.

Rather than attempt to incorporate short-term metrics into balanced scorecards, Thinklong should encourage marketers to remove them entirely from the measurement of long-term brand campaigns.

Instead, the focus should be on evaluating, after a period of at least 12 months, the impact on price elasticity and the change in market value share, in addition to the total payback, rather than the immediate ROI.

Marketers should also measure the subsequent buying behaviour of people that were recruited via activation spend versus those who purchased following brand campaigns.

This will further validate the evidence to support the latter and ensure investors are less enamoured with short-term metrics like cost per acquisition.

5. Reposition brand communications as a capital investment

We face the considerable challenge of a century of stagnant communications expenditure.

Since the 1920s, the US advertising industry has averaged 1.29% of GDP, falling between a narrow range of 1 and 1.4%. A similar pattern occurs globally.

New media has never increased budgets, merely shifting how existing money is split, with the ratio of sales to adspend remaining ‘stubbornly flat’ at 3.5% for nearly 100 years.

In contrast, other components of company spending have fluctuated greatly. This suggests we must be more aggressive in stealing share from elsewhere. A zero-sum game requires us to not only position brand communications as the safest path to growth but question other costs.

Yale economist William Nordhaus, for instance, demonstrates that ‘only a minuscule fraction of the social returns from technological advances was captured by producers (just under 4%)’.

In other words, the beneficiaries of innovation are nearly always consumers rather than companies and their investors.

As the late Andrew Ehrenberg stated: ‘Successful product innovations tend to benefit the consumer. The producer may hang on to some early-mover gains but innovation is not the stuff of effective long-term competition, except defensively.’

Uncertain times entitle investors to call for reduced capital spending in costs that are unlikely to deliver a return. By demonstrating communications is a safer investment, budgets will be less likely to face the axe.

Besides being plagued by ignorant quotes about half of advertising spend being wasted – an oft-repeated statement that fails to understand the financial value of making the brand more famous - the fundamental problem of being a creative endeavour is that it’s perceived as inherently risky.

More broadly, marketing is still seen as a cost rather than an investment by business leaders, according to more than half of marketers.

Given the rising economic uncertainty, we must be prepared to embrace a new way of thinking that positions advertising as the most conservative of investments: effectively enabling companies to purchase growth.

As Bullmore said: ‘If the medium you’ve chosen reaches the people you want to reach, and if your medium clearly carries the name of your brand, your money will not have been wasted.’

Thinklong’s ambition must be to reposition long-term advertising expense as a capital investment, integral to profit growth.

Marketers should also be prepared to question management as to whether other expenditure are riskier undertakings, less likely to result in a profit.

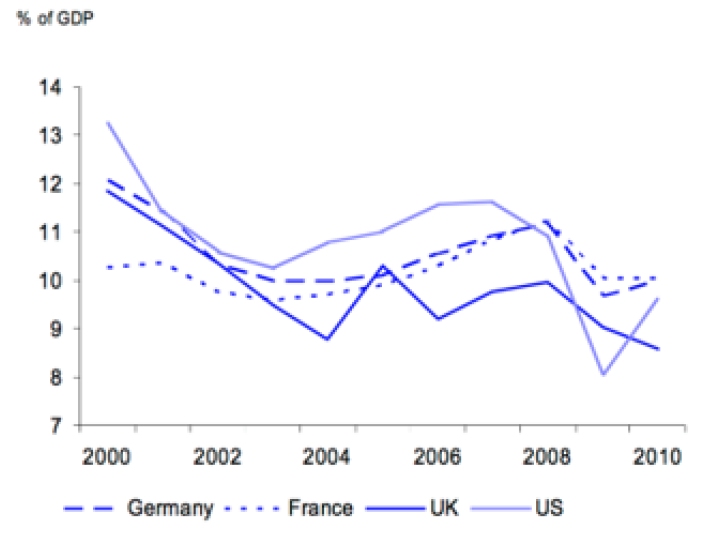

Fig 1: Business investment as a % of GDP

The decline in business investment means all expenditure increasingly becomes a zero-sum game that requires all costs to be more robustly defended.

6. Prioritise media that carries brand value

One of the main advantages of TV is that it's a costly signal19. A company that didn't believe in what it was selling, or who planned to cheat consumers in any way, would never waste so much money communicating a brand name to so many.

As Rory Sutherland highlights, ‘As Seen On TV’ conveys something “As Seen On Facebook” does not.

People have never trusted advertising but they have always trusted brands that advertise through mass media. Few brands have found fame without it.

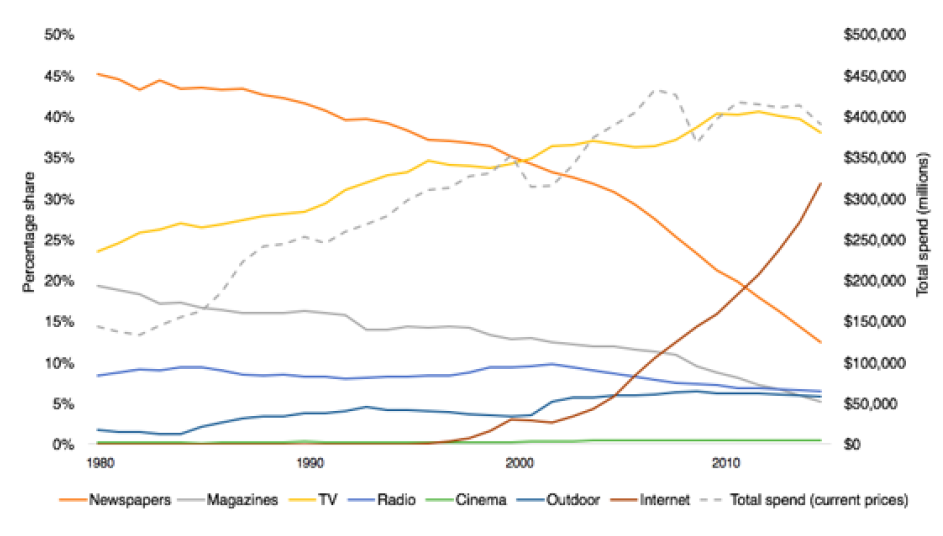

Having started attracting small communications budgets in the mid-90s, the internet’s share of total adspend rapidly grew to 32% by 2015 (see figure 2). comScore estimate that direct response accounted for 80% of that spend.

Across that same period, total spend in current prices remained relatively flat. Print media suffered most, with newspaper’s share falling from 36 to 12% and magazine’s down from 13 to 5%.

With Zenith predicting digital will surpass TV in global adspend for the first time this year, we must remain alert to the implications of that shift in spend.

Field (2015) has discovered a strong relationship between the level of digital channel usage and campaigns designed to achieve rapid sales effects. Indeed, across that period of steepest growth in digital expenditure, Enders Analysis found the share of advertising spent on activation climbed from 39% (in 2000) to 49% (by 2016).

Despite this, the latest research from Binet and Field (2017) demonstrates the 60:40 brand/activation budget spilt continues to deliver the biggest financial payback.

The pursuit of more cost-efficient and targeted reach is evidence of our own short-termism in action.

While Thinklong should never favour one medium over another - effective strategies are inherently media neutral - I believe it should support the principle that brands are built through trusted media.

This requires it to support media that invests in quality entertainment and/or journalism. While it’s not for Thinklong to determine what qualifies as such, I believe we must tackle the rise of websites that use cookies to, in effect, steal traffic from established publications. This becomes particularly important as more spend moves towards digital and more traditional media becomes digital in format.

Thinklong must therefore encourage agencies and marketers to commit to:

i) Put media before eyeballs

Increasingly, publications are losing a significant share of revenue to adtech intermediaries.

Mediatel reports that in worst case scenarios, for every pound an advertiser spends programmatically on the Guardian only 30p goes to the publisher.

Adtech uses cookies to track individuals visiting reputable publishers to identify where it can reach them for less.

Alexis Madrigal writes: ‘The ad market, on which we all depend, started going haywire. Advertisers didn’t have to buy The Atlantic. They could buy ads on networks that had dropped a cookie on people visiting The Atlantic. They could snatch our audience right out from underneath us.’

Doc Searls believes that ‘adtech is built to undermine the brand value of all the media it uses, because it cares about eyeballs more than media.’

Indeed, an ad for JP Morgan Chase recently appeared on a website called ‘Prison 4 Hillary’ - an unintended consequence of chasing cheaper impression.

Disregarding the context of the placement of an ad to reach the same person for less elsewhere, ignores the fact the signal is proportional to both the content of the ad and the value of medium it appears within.

In addition to providing signalling value, advertising on digital newsbrand sites is 80% more likely to be viewed than advertising on non-newsbrand sites.

Rather than building an endless list of sites to block, advertisers must focus their investment on media that carries brand value. All digital reach is not equal in its effectiveness.

ii) Embrace the use of tracking protection tools

Tracking protection tools enable users to block sites from sharing personal information with third parties. This prevents people from receiving ads targeted at them based on their personal data.

As Don Marti highlights, the less targeted advertising is, the more valuable brand advertisers will find it: ‘Brand advertisers need to send a credible signal, and tracking protection for users helps reinforce that signal.’

The more people an ad reaches, the more advertisers will invest in production value. When the concern is with improving the response rate of the 0.0x%, you pay little attention to the 99.9x% you’re irritating. The focus is on nudging the people ready to buy into doing so, with engagement defined by the effect upon the fingers of the few, rather than the minds of the many.

Thinklong is in the business of representing the long-term interest of brands. While encouraging tracking protection may not be in the interest of direct response practitioners, it benefits higher-value brand advertising. As such, it should receive its support.

Fig 2: Trend in adspend by media type & total spend (current prices)

7. Encourage non-linear thinking

In an article in Harvard Business Review, de Langhe et al (2017) reference several research studies in cognitive psychology that demonstrate how the human mind struggles to understand non-linear relationships.

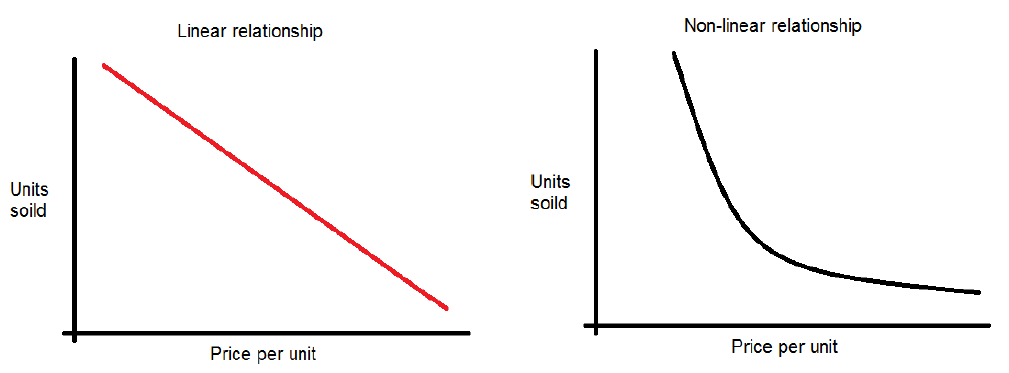

Despite the evidence for price having the biggest effect on profit, managers still focus more effort on driving volume by reducing prices; believing profit to be a linear function of sales (see figure 3).

As the authors highlight, the thrill of seeing immediate volume gains clouds their judgement and leads them to underestimate just how large those increases must be simply to maintain profits.

Researchers at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute recently conducted in-depth interviews with a range of managers to explore the factors behind price-promotion decisions.

They discovered that intuition and untested assumptions were the main inputs, often being made in ‘stark contrast with academic knowledge about the effectiveness of price promotions’.

The failure to account for non-linear patterns is a significant factor in why managers focus on immediate returns at the expense of more profitable gains in the long-run.

Thinklong should plan training courses to educate agency employees and their clients in understanding linear bias.

Data visualisation also helps people make better decisions by making the threshold points at which outcomes change easier to grasp. Including an interactive tool on the Thinklong website is one way to illustrate and apply this.

This will ensure agencies and marketers better recognise and reflect on whether their own actions are conducive to the long-term interests of the brands they work for.

Fig 3: The relationship between price/sales volume and profit

Fig 3: The relationship between price/sales volume and profit

We imagine the relationship between volume and price in delivering profit to be linear (the red line indicating the imagined profit relationship between units sold and price per unit) but in fact it is non-linear (the black line indicating the actual profit relationship between the two).

Large volume increases are required simply to cancel out a small reduction in price. Conversely, small increases in price can deliver disproportionate profit growth.

Conclusion

Research from the American Association of Advertising Agencies found that advertising affects just 5% of a company’s stock value directly. However, it has an indirect effect on 75%.

Similarly, many of the ways in which we can ensure brand communications’ role in delivering profit growth is better valued are best achieved indirectly. As Kay highlights, the path to achieving complex goals lies in obliquity.

Anything that nudges investors and executives into focusing on longer-term growth will ensure strategies and activities that support the achievement of it will be more highly valued.

The role of a brand in delivering future profit to a company is clearly established. However, marketing communications’ ability to build them remains less understood.

While the priority must be collective action to achieve behavioural change, like any effective advertising campaign, we must also defend our share of budgets, nudge and remind key stakeholders of the value we bring, and look to steal share from rival costs.

Once behavioural change is achieved, I believe the marketing communications industry will be best placed to capture the increased investment that follows, with brands the biggest beneficiaries.

Gareth Price is a Strategist, Facebook. This essay earned him a distinction on the IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands. The 2026 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands is now open for applications.

View the full syllabus and submit your applicationThe opinions expressed here are those of the authors and were submitted in accordance with the IPA terms and conditions regarding the uploading and contribution of content to the IPA newsletters, IPA website, or other IPA media, and should not be interpreted as representing the opinion of the IPA.