As part of the 2022 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands, Red Brick Road's Lisa Gulley explores how thinking counter-intuitively about brand behaviours: embracing the discomfort of pain, truth and the temptation of others, will bring brands and their audiences back together again.

If ever there was a song that captured how it feels to be in a relationship where the two sides see things so differently, it’s Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Go Your Own Way’, written in 1976.

Fleetwood Mac rented a house in Florida to start working on ‘Rumours’. It wasn't the best time for the band. Two relationships between band members were crumbling. Lindsey Buckingham was separating from Stevie Nicks. John and Christine McVie were soon to divorce. The house had a bad vibe to it, which only added to the tension (Fleetwood, 2015).

In that house, Buckingham wrote the hit record ‘Go Your Own Way’. It was an angry song responding to Nicks’ decision to leave. Nicks said that Buckingham’s controlling behaviour drove her away. Buckingham failed to see it. His song was both a masterpiece in song writing and delusion.

The disconnect between Lindsey and Stevie has gone down in rock and roll history. The couple remained in the band, warring through hit songs, never quite healing the rift.

Brands too are drifting from their audiences and can’t seem to see it. Brands are making grand promises. Buyers have become cynical about what they’re told.

Brands are getting side-tracked by the issues of the day. Buyers are calling them out for it. Brands are desperate to remain relevant and fashionable. Buyers are onto the next big thing.

Brands and their audiences are living not just in separate rooms, but in separate realities.

Which makes the brand-consumer disconnect an urgent issue. Hegarty’s advice is timeless: “the key to great marketing is never to stop thinking like your audience” (2017). There’s a need for many brands to go back to basics before jumping into the metaverse.

Because things are getting rocky. Despite having higher expectations of brands than in the past, consumers aren’t happy: “three-quarters of consumers globally think it is now harder to trust what brands say and do” (Ford, 2020).

Havas thinks brands need to do some soul searching “71% of consumers are tired of brands’ empty promises” (2021).

There are two sides to every story. Never have brands faced such impossible conditions to survive and thrive. The level of competition is stratospheric. Mental and physical availability is challenged. Media fragmented. Short-termism rife.

Brands are compelled to court attention through whatever means possible. The brand relationship is left playing catch up in the game of visibility.

Esther Perel is a world-famous couples therapist, author and TED Talk champion (2015). She’s also a realist when it comes to relationships. She believes that couples grow closer when they learn to live with pain, radical honesty and the temptation of others. It’s uncomfortable stuff. It’s also a wake-up call for brands.

Brands would benefit from couples therapy.

Bad behaviours

Of course, people don’t have ‘relationships’ in a human sense with brands. But the relationship analogy is useful from a brand point of view, even if the feeling isn’t mutual. Brands seek intimacy and desire to make their audiences feel understood. Much like good spouses do.

And like couples, brands are expected to keep their promises, keep things fresh and honour their ‘partner’ come what may. But reality bites. Commitment wanes. Relationship issues set in.

Let us consider the ways in which brands are being ‘bad partners’:

Empty Promises

Making empty promises about a product or brand experience won’t wreck the relationship overnight but it will be a brand’s undoing over time. It’s a special kind of magical thinking that hopes an audience doesn’t bring real life experiences into the equation.

Unreliability

Brand extension which is inauthentic and confused makes for a very unreliable partner. Trying to appeal to everyone rather than demonstrating a deep understanding of the audience you love will kill the spark. Over time, indifference sets in and brand fans move on.

Neglect

Poor attention paid to the product or customer experience pours weedkiller on the relationship. However unintentional, insensitive and harmful brand moves deny the reality of an audience and call time on the relationship.

Changing the Subject

Resentment also builds when brands change the subject and busy themselves with pseudo-purpose “claiming to try and solve an issue… that their social listening data says is trending with their demographic that month” (Roach, 2020). This is especially damaging when it co-occurs with the avoidance of problems a brand should be solving.

Half Truths

The climate crisis is the difficult conversation brands are trying to have. There are no shortcuts but brands are jumping the gun for brownie points, hoping no one gets the red pen out. Audiences feel angered by statements that later turn out to be half true or false.

A sort of brand truthiness has taken hold: “stating concepts as one wishes or believes to be true, rather than the real facts” and it’s undermining the relationship audiences have with brands (Colbert, 2005).

Brands are straining under growing consumer expectations, drifting from what matters, wrapped up in fantasies of their own making.

Consumers are left questioning their commitment and seeking a fresh start.

People don’t care… do they?

There’s the argument that none of this really matters.

Net Promoter Scores suggest that most feel neutrally about brands, not moved to promote or detract. With 500,000 brands in the world, buyers aren't going to lose sleep over any one brand (Nielson, 2021). Experts are keen to remind us “nobody really cares about our brands” (Ritson, 2021).

So why should it matter that Dove made some funny shaped bottles of body lotion? Who cares if Coke changes the formula a little with New Coke? And it should be no cause for concern when Disney keeps quiet about Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill? Buy a new lotion, choose a different soda, max out on another rollercoaster.

Except these burst bubbles mattered. Dove stopped being real about beauty. Coke failed to refresh the world with New Coke. Disney became selective about who could be happy in the happiest place on earth. It mattered. People cared.

It should matter to brands too because once the line is crossed “40% of people globally would try to dissuade friends and family from doing business with companies they don’t like” (Ford, 2020).

The banana skin for brands is comforting themselves that people don’t care and aren’t paying attention. Because suddenly they can, and suddenly they are.

What can we make of this paradox?

People care… about betrayal

We know that brands are mental shortcuts. People like what fits; what is comfortable and familiar. Cognitive ease puts people in a good mood. The opposite is true when things don’t fit. Cognitive strain makes a person more likely to be vigilant, suspicious and uncomfortable with a situation (Kahneman, 2011).

But consumer reactions are more than just discomfort. Audiences act as if betrayed.

Perel gets to the bottom of this in her work with couples. She explains that betrayal is a violation of what’s been agreed “we expect our partner to act according to our shared set of assumptions, and we base our behaviour on that” (2017).

In a brand context, audiences also feel betrayed because a contract is broken. Betrayal messes with expectations. Brand trust then hangs in the balance.

We should take it seriously because two-thirds of consumers globally say that once trust is lost “there’s no getting it back” (Ford, 2020).

And maybe it goes deeper that that.

Betrayal threatens our sense of self

Robbing someone of his or her story is the greatest betrayal of all.

Perel explains that infidelity shakes the foundations of a person’s identity. When a spouse is betrayed they suffer the loss of a coherent narrative. Clinical Psychiatrist Ana Fels defines it as the loss of an “internal structure that helps us predict and regulate future actions and feelings (creating) a stable sense of self” (Perel, 2017).

Infidelity attacks our memory of the past. Leading Fels to conclude: “it not only hijacks a couple’s hopes and plans but also draws a question mark over their history” (2013).

Which means betrayal matters because it threatens a person’s sense of who they are and how they get there.

It’s an insight that’s critical to brands. People build their identities around brands, much like they do with relationships.

When brands drop the ball, it’s an attack on a person’s identity. Their brand choices suddenly betray who they believe themselves to be.

It can be socially embarrassing. The Looking Glass Self explains that self-image comes from how we think others see us, and that crucially, we play an active role in trying to shape how others see us (Cooley, 1902). So, when brands betray our expectations, it doesn’t just undermine that self-image, it pumps out the wrong social signals.

Is it any wonder consumers get mad?

Starting over: three uncomfortable commitments

It is magical thinking to expect brands to be the perfect partner. The brand building context will lead them off course. Reputational missteps will happen. But even the biggest betrayal can be turned around if brands are prepared to change their ways.

Perel believes that couples grow closer when they are prepared to live with discomfort and uncertainty. I believe salvation for brands lies in the same.

Inspired by Perel’s teachings, brands should embrace three shifts in mindset:

- Embrace pain: from swift apologies to recollection of wrongdoing, repetition, and remorse

- Embrace truth: from being a closed shop to an open book, trusting consumers can handle reality

- Embrace temptation: from jealously guarded consumer relationships to open and non-exclusive partnerships

It will be counterintuitive for brands used to projecting authority, confidence, and certainty. But it’s time for brands to zag. The new context “requires an unnatural act… we need to abandon the comforts of habit, reason and the approval of our peers and strike out in new directions” (Neumeier, 2006, 76).

The best brands have always zagged. Marketing has always with shifted with consumer priorities. It is time to do it again.

Embrace pain

The wanderer is usually all too eager to put the unpleasant episode behind them. By reversing these positions, we change the dynamic

How a couple metabolises an affair will shape the future of their relationship. Perel encourages both sides to keep talking about what went wrong. By holding onto the memory and sharing the burden of suffering, it releases the injured party from replaying events. Therapist Abrahms-Spring explains this as a “transfer of vigilance”. The simple act of remembering and repetition “helps restore coherence and is intrinsic to healing” (Perel, 2017).

When a brand’s indiscretions come to light, consumers too can be left “grappling with the fact that they have been living in different realities and only one of them knew it” (Perel, 2017). It is an imbalance of power, in favour of the brand. It doesn’t feel good. So how brands work through painful events will determine future intimacy.

There are many great examples of brand apologies. Embracing pain, however, looks past the apology and suggests holding onto the pain. It’s an uncomfortable shift in mindset for brands trying to compete and win but it is “a sharing of the burden of suffering” and “a restoration of the balance of power” (Perel, 2017).

By trading places and freeing consumers from rehashing a crime, the dynamic is changed. People will still lash out. But demonstrating greater levels of empathy will heal and build more stable foundations for a brand than hurrying to forget.

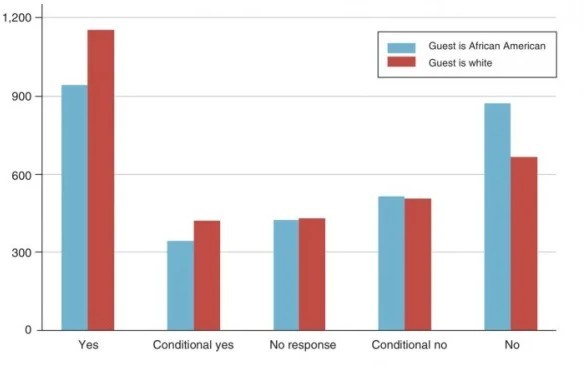

In 2015, Airbnb was urged to take responsibility for the racial profiling and discrimination taking place on its site. People were sharing their stories of discrimination using the hashtag #AirbnbWhileBlack. The promise of belonging in tatters, the CEO issued an open letter titled “Discrimination is the Opposite to Belonging” (Chesky, 2016).

It was a carefully crafted apology, but they didn’t leave it there. Two years later the brand showed up in the Super Bowl ad break asserting the “The world is more beautiful the more you accept”. Since then, they have removed 1.5m hosts and users from the platform for discrimination. They continue to talk of “finding and fighting discrimination” (2020).

Like Airbnb, some betrayals will need brands to sit with pain and share in the suffering. Whether offender or spectator, a brand’s recollection of wrongdoing, repetition and remorse can be powerful and healing. Brands should do what feels unnatural.

Mary Portas describes the era in which brands now operate as the “era of sentience”. It’s a new mindset for brands to get their heads around because success is now “built on the so-called soft stuff that previously had no place in business, in the boardroom” (2019).

Embrace truth

Once the fiction has been cracked and you are no longer protecting it, you can begin to craft a more truthful narrative together.

Perel describes a type of couple who grows closer in the wake of an affair. “Explorers” become fully open in their communication: engaging in brutally honest, vulnerable and emotionally risky conversations. They get comfortable with uncertainty and “accept that trust is a leap of faith” (Perel, 2017).

Linguists Wilson and Sperber make a case for truth by underlining the danger of fiction in communication, explaining that communication is successful “when emitter and receiver share exactly the same code. Any difference between the emitter and receiver’s codes is a possible source of error in the communication process” (2012). If brands avoid the truth, reality will mess with the code.

Feedback and truth are baked into some professions. Writers have editors. Athletes have coaches. Actors have directors. Brands have consumers but they’re not letting them in. Ways to be more open and truthful:

Dare to be Vulnerable

Nike was one of the first to openly support the Black Lives Matter movement. It called on people to stand together in the fight against racism with a social media post telling the world “For once, Don’t Do It”. They followed up by opening up, confessing they could be doing more to champion black communities and employees.

Speak the Unvarnished Truth

The Gym Group has recently punctured the pretentiousness of the fitness category. It has been refreshing for a fitness brand to talk about the ugly truth of exercise. Embracing brand imperfections and flaws can also make a brand more likeable and “works especially well when competitors are braggarts” (Shotton, 2018).

Stop Hiding Behind Words

Patagonia has promised not to hide behind the word “sustainable” after recognising that carbon neutrality isn’t doing enough to erase the footprint they create.

Unilever has dropped use of the word “normal” to describe skin, recognising that the word leaves many buyers feeling inadequate or skin-defective.

Be Disagreeable

El-Gammal thinks brands should “be brutally honest and accept that not everyone will like it” (2020). Being disagreeable is being honest. You’re not being truthful by trying to please everyone. Diesel demonstrated this when they celebrated losing 14,000 followers after posting Pride content, writing: “Followers are important. But love is more important”.

Reflect a Deeper Truth

Gucci Beauty chose model Ellie Goldstein because it was time for more models with disabilities. But it also reflected her truth. Ellie grew up wanting to be famous and loved attention. Having Down Syndrome didn’t stop Ellie feeling like other girls her age.

Rake Over the Mud

Eyewear brand Ace & Tate launched a campaign lamenting its past mistakes before becoming a B Corp. It was a warts-and-all account which carried the headline: “Look, we f*cked up”. Each mistake was hung out like dirty washing and labelled a “bad move”.

Today the world wants truth. Documentary is enjoying a golden age. Autofiction is now a thing. But trust in institutions, politicians and platforms has decreased to such a point that, on average, people believe that they need to read 5 sources to feel like they know the truth (McCann, 2017). If brands aren’t authoring their truth, you can bet on consumers finding it regardless.

Embrace temptation

Each of these long-standing couples has chosen not to ignore the lure of the forbidden, but rather to subvert its power by inviting it in.

Perel thinks there’s a great strain on the modern relationship. A partner is expected to offer stability, safety and predictability, and at the very same time supply awe, mystery and adventure. Perel despairs that the monogamous partner demands “give me comfort and give me edge. Give me familiarity and give me novelty” (2017).

It’s a predicament brands find themselves in with consumers. Consumers want it all and are being seduced at every step. Brands are buckling under the pressure to satisfy.

But comfort and edge are possible if we challenge how we see the boundaries of a brand. Polyamory works for cosmopolitan couples. They engage in multiple romantic relationships at the same time, with the knowledge and consent of everyone involved. There is evidence that taking off the handcuffs is working for brands too.

When the power of others is at its most potent:

Unanticipated Collaborations

Brand advertising will always be at threat in a downturn, despite evidence that going dark is to be avoided (Field, 2021). Unexpected and ‘sinful’ collaborations are a way around a shrinking media budget, and a way back into consumers’ hearts. Fashion brands do it best.

When Vans trainers started something with Disney’s Mickey & Friends eyebrows were raised but new levels of satisfaction were achieved, amongst fans of both cartoons and sneakers.

Brands as a Blank Canvas

Some brands offer their brand as a canvas for perpetual re-expression. In the years since Absolut turned their bottle into art, the approach is being used effectively to communicate forgotten or ignored brand provenance.

Dolce & Gabbana has recently ‘wrapped’ the Smeg mixer to remind people of the Italianness of Smeg.

Category-busting Creations

Unlikely brands working together opens new revenue streams through the creation of brand-new categories. “Solving real consumer problems with imagination and flair becomes more possible when brands open up to outside-in thinking” Brands in adjacent categories will suffer from groupthink, so cast the net further (Grant, 2016, 178).

A brilliant example is the love child that is Balenciaga and Bang & Olufsen’s speaker bag.

‘Why Brand’ Chemistry

While 76% of marketing leaders say their organisation has a defined purpose, just one in ten say it’s being systematically activated (Sweeney, 2018).

Getting into bed with brands sharing similar beliefs can give the “why brands” a how, and more marketing investment to drive the changes (Sinek 2009).

Protecting and nurturing childhood is a gargantuan task, even for Lego. A long- term partnership with Epic Games shaping the future of the metaverse means sharing the glory but doubling chances of success.

Temptation Rekindles

Perhaps the most persuasive argument of all is how temptation can resuscitate a brand. Strong brands can use it to deepen relationships. But waning brands can use it to rise from the ashes and dust off what was once great.

In 2020, M&S launched its “never the same again programme”, kicking off with a series of strategic and tactical partnerships, guest brands, collaborations and new routes to market. There is much more to come. A brand under immense pressure, they see a polyamorous future as the most profitable future.

Back in the 80s, Polaroid promised “Polaroid means Fun”. It lost its way and filed for bankruptcy in 2008. But in 2022 the brand is back with a vengeance thanks to a stream of collaborations with Pepsi, Keith Haring and Saint Lauren. The latter retails at £775.

The spark of others is a necessity in this new brand climate and no longer a luxury. Ignoring the reality that consumers’ desires are being shaped by others is a slippery road to irrelevance. Better to subvert the forces of temptation by inviting them in. Brand narratives become richer and more interesting in the process.

Conclusion

Brands have been drifting from their audiences. Patching things up will require brands to shift how they think and behave. Existing brand behaviours will deepen the chasm and push buyers further away. New behaviours are called for. I believe we have entered a new marketing age of sentience and empathy.

People are desperate for brands to pay attention and listen, truthfully respond, and know their limits.

What works for couples can work for brands. There is no guarantee of a happy-ever-after, but we have the present and change can start today. Brands will get closer to audiences by: sharing in the pain when it happens; committing to radical honesty and emotionally risky conversations; and embracing the seductive power of other brands.

Brands must learn to love differently to become stronger. Therapy is painful but break-ups are worse.

This essay was submitted as part of the IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands. The 2026 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands is now open for applications.

View the full syllabus and submit your applicationThe opinions expressed here are those of the authors and were submitted in accordance with the IPA terms and conditions regarding the uploading and contribution of content to the IPA newsletters, IPA website, or other IPA media, and should not be interpreted as representing the opinion of the IPA.