It makes sense, doesn’t it? Investing in advertising should get you into a position where you can put prices up without losing all your customers. If advertising keeps your product familiar, signals that many people buy it, or conveys information about quality, it should mean you can charge more.

Marketers believe it, but because we’ve had decades of stable prices, we haven’t had the evidence to prove it. But that changed this year. We’ve now lived through a recent period of inflation, where a wide range of businesses have had to put prices up. And, at IPA Effworks Global 2023, there was a read out on how it’s gone.

Evidence from econometrics and case studies all points in the same direction.

Investing in advertising helps protect sales when businesses raise prices. And over time, businesses that outspend competitors find that customers’ tolerance to their price increases improves.

These are valuable lessons for right now, because inflation won’t go away overnight. Even the most optimistic economists think price rises will be with us for most of 2024.

Stronger brands can charge more

Let’s say you put your price up. If you only lose a few sales that’s good. Your revenue might stay the same, but you’ve had to make less stuff, or provide fewer services. It’s better for profit.

On the other hand, if the price rise means you lose a huge number of sales, it’s obviously bad.

Econometrics measures the effect of price on volume sales using price elasticity: The percent change in volume for a 1% increase in price. It’s always going to be negative – price goes up, sales go down - but you want it to be as near to zero as possible.

The chart below shows that this is the outcome you get if you’ve spent lots on advertising.

Across 40 FMCGs, where price elasticity was estimated using econometrics, price elasticity gets closer to zero as media spend increases.

FMCGs that advertise more have customers who are tolerant to price rises

Now you might be wondering whether this is really a causal relationship. And you’d be right to say that you can’t tell just by looking at the chart above.

It could be that other factors - like product, price, and business size – are driving both advertising and price elasticity.

Those factors may well matter, but the evidence points to there being a direct causal effect too.

The chart below shows the case of three FMCG brands of a similar size, in the same category, with the same owner, over the same period of time.

The business decided to back brand C with a punchy +9.3% excess share of voice, while neglecting brand A to the point that excess share of voice was negative at -2%.

Spending on advertising reduces your sensitivity to price rises

The chart shows that, over the 3 years in the study, brand C’s price elasticity improved to the point where price rises would be profitable, while brand A’s worsened to the extent that price rises would be a disaster.

Two case studies of modern brand building that reduced price sensitivity

Two more detailed case studies come from our clients at Magic Numbers: Yorkshire Tea and Little Moons. Even though they have different strategies, both have built strong brands, and both have category-beating price elasticities.

2023 Grand Effie winner Yorkshire Tea built its brand the traditional way, with a strong creative idea delivered in an entertaining way on TV. Like brand C in the case study above, it maintained positive excess share of voice over many years.

The result was that it not only grew to be the tea category leader, but throughout its growth it maintained a premium price position.

And, when in response to its rising cost base, Yorkshire Tea was forced to increase prices in June 2022, the reduction in sales was modest. Econometrics showed that its price elasticity was 25% below what’s normal in FMCG. In 2023, the brand cut its media spend, but its previous long-term investment in brand building will almost certainly help its performance until the brand's advertising budgets are restored.

Little Moons’ brand building story was quite different. Its strategy was to create a mochi ice cream product and brand that people wanted to spend time with.

This, combined with a bit of luck, brought a viral moment of brand building on TikTok, with platform native creators producing content. Little Moons then built on this momentum with successful advertising and a series of events and activations.

Even though the story was quite different, the result was the same. Little Moons has experienced very fast growth, while maintaining a price point above other ice cream. Its price elasticity is a full 35% below the FMCG category benchmark.

Brand building isn’t the right choice for some categories right now

The advice from the above analysis seems pretty clear. If you’re going to need to put prices up, invest in your brand first.

But there is a proviso to it.

Inflation causes demand to drop in some categories more than others. And if you’re in one of those that’s worst affected, you might be wiser to wait.

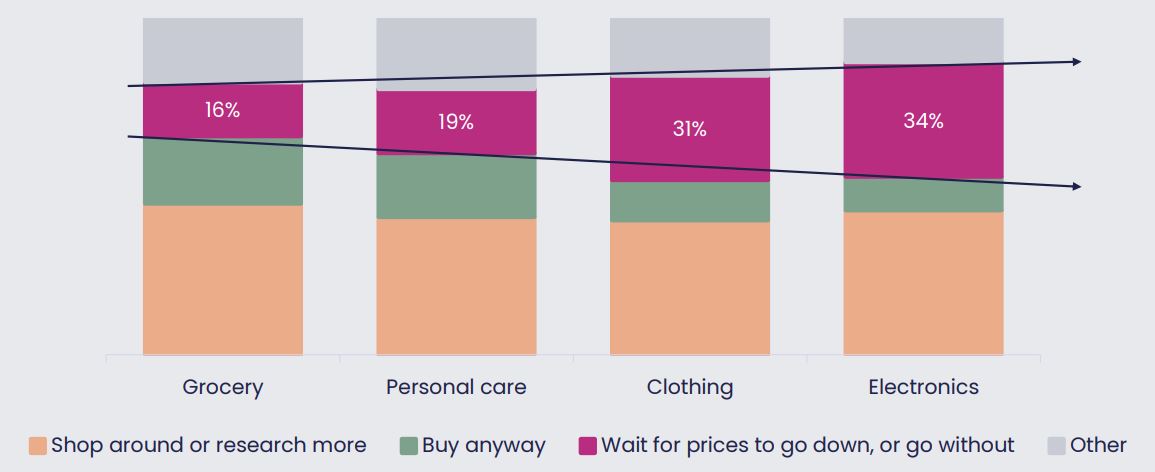

The chart below uses data from WARC’s recent trends survey, which asked 15,000 people what they would do if they wanted to buy an item that had increased in price from 6 months ago.

Categories are ordered from left to right based on how necessary the product is. And the proportion who would halt their purchase increases rapidly the more discretionary or non-essential the item is.

If you wanted to buy an item that increased in price from 6m ago, what would you do?

In necessity categories, like grocery, shoppers have to buy something from the category even if prices have gone up. But in categories where the product is a treat, like a new electronic item, demand during inflation can be down by as much as a third.

Share of voice/share of market analysis combined with a forward-looking view of your category’s prospects in 2024 is a wise way to establish whether brand building is right for you next year, and if it is, how much to spend.

Magic Numbers hosts a free tool to help marketers run the numbers

A final word about hunches

So, it turned out our collective hunch about the effect of advertising and price sensitivity was bang on the money.

That shouldn’t be surprising. Marketing people are generally wise, and work hard to understand existing and potential customers. Not all of what we learn is in spreadsheets, debriefs, and white papers.

But there are significant benefits to businesses in having evidence that tests marketers’ hunches and quantifies the size of effects.

The IPA’s recent publication on econometrics in the C-suite is full of examples and case studies where marketing people have been able to get the next steps they believe in – across advertising and price - accepted at the most senior level. Because they aren’t just presenting their hunches, they’re bringing good evidence.

And we’re all far more powerful if we’ve got both in our back pockets.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author and were submitted in accordance with the IPA terms and conditions regarding the uploading and contribution of content to the IPA newsletters, IPA website, or other IPA media, and should not be interpreted as representing the opinion of the IPA.