As part of the 2022 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands, UM Worldwide's Ruth Corrigan examines the inherent gender bias that pervades our industry, and argues that to restore credibility and safeguard the future of our craft, we need to find a more equitable solution and that the answer lies in changing behaviour to harness the collective voices within our industry.

Timnit Gebru, an expert in AI ethics, stares at the email in front of her and nervously pulls the trigger. It is November 2020 and she has just unleashed a tidal wave that will have ripple effects reaching the US Congress. Gebru discovered an inherent bias in the facial recognition technology she was developing. Rather than conceal the flaw, she shared a paper denouncing it, hoping to raise awareness and prevent the bias seeping into future AI systems. The response? Gebru was publicly ousted for her treachery from her employer, Google (Mahdawi, 2021).

Next, we time travel to the pop culture era of the 1980s. An advertising exec is concocting his latest ad campaign to reach older women (Walsh, 2017). Little did he know he would birth a word that would be socialised around the world, impacting the representation of older women for generations. This year, the Body Shop finally banned this terminology from their range (Ormesher, 2022). The mere ten letters that unleashed decades of psychological anxiety to sell more products? Anti-ageing.

Now, a final trip to the classroom in modern-day ad-land. The ‘brand leaders of tomorrow’ are concluding a qualification that will sharpen their strategic thinking (IPA, 2022). Equipped with a reading list starring our industry’s leading legends, the delegates are educated on the foundations of marketing theory, from Stephen King to Byron Sharp. But one student couldn’t get beyond the glaring gap in the authors, content and case studies listed. Despite 67% of our industry being female (ANA, 2021), only 6% included women (IPA, 2022). The course in question? The IPA Excellence Diploma.

What binds these individual cases is the collective gender bias still prevalent at the heart of our industry. Whether exacerbated by the AI systems controlled by tech monoliths, the tireless efforts to redress harmful language from our communications, or the foundational theory educating our future brand leaders.

While gender equality is not a new issue – in fact, it’s so old that two-thirds of men believe it has already been solved – I believe the problem is inherent in who we’re near exclusively learning from (Edwardes, 2021). What brand lessons are we missing out on because we are primarily gazing through the lens of one gender? How can we ever reach a truly representative position if female voices are so absent from our academic learning.

This essay will highlight the impact of this lacking female lens and extract valuable lessons from those already defining a future state. I believe the female voices are already there, but until we rebalance the systems and structures in which our industry is founded on, we are ill-equipped to solve this problem. As I write this, I am mindful of my own bias as a female in the industry, who has been culturally primed to think in a certain way. This is why I have integrated the core tenets of our marketing theory with a collective of female voices, to show that together we can craft a more progressive and solution-orientated model for brands. As a creative industry, we are the best poised to do so.

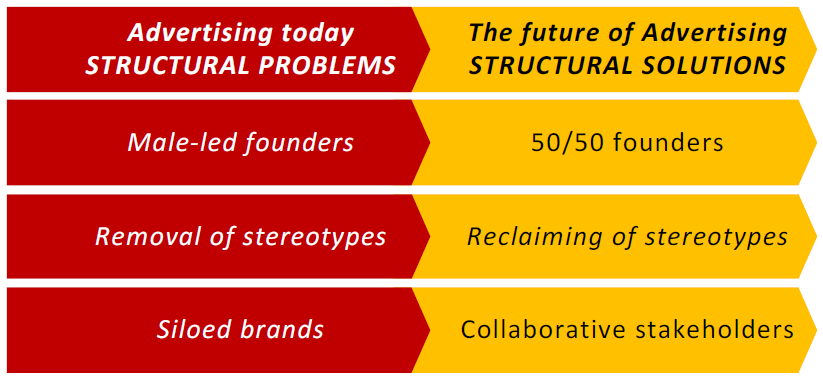

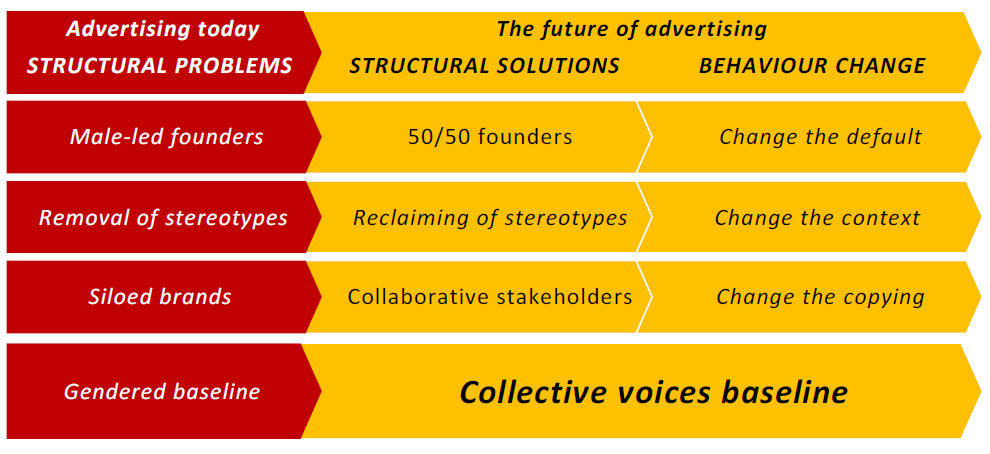

Identifying the structural problems

There is already a huge amount of tangible progress for women in advertising, championed by great organisations pushing these issues forward. WACL, Bloom, The Unstereotype Alliance, Creative Equals and the IPA all celebrate female role models, give support to and campaign for women’s issues. But we have to recruit more men to recognise and help fix these biases. As Mums In Ads founder (MIA) recently bemoaned, ‘where these guys are, how we find them and exactly how we get them on board with our initiatives… we have no bloody idea’ (Spencer, 2022). I believe we need to look beyond advertising to understand where the inherent systems and structures are still holding women back.

1. Venture capitalists control the next-gen brands

Venture capitalists (VCs) prepare start-ups before they IPO. These early stages are critical for a business and sow the first seeds of a brand. Janice Cargo, DTC investor for the VC firm Active Partners said that a visionary founder is the most important thing an investor looks for. A founder is ‘the brand’s magic,’ and their passion and dedication will play a pivotal role in the success of their business (Cargo, 2022).

One such founder is Whitney Wolfe Herd, whose dating app Bumble made her the youngest, female self-made billionaire in history. Whitney is no female outlier. In her book ‘The Authority Gap’, Mary Seighart quotes that ‘VC firms that hire more women as partners have 10% more profitable exits and women-run private tech companies earn a 35% higher return-on-investment. Yet, companies run by men still win 93% of all VC funding.’ (2021).

This has a ripple effect on the diversity of our industry, when a female leader is more likely to think of and account for female nuances in their products. Apps like Mush, which bring new mums together. Or Bubble, the Airbnb for childcare, helping mothers get back into work while they still shoulder the majority of childcare. What other valuable products are we missing out on, because only 7% of the businesses that start out are led by women?

This problem is not for lack of female options. Serena Ventures investments was founded by Serena Williams to increase diversity in VC funding. To date, 76% of its investment has gone toward under-represented founders, with 53% of the overall total towards women (Anon, 2022). Imagine if all VCs added a 50/50 diversity quota when assessing their next ‘magic’ founder?

I believe investing in more female founders will create more female role models in leadership, more products solving female problems and more brands reflecting female points-of-view. All generating case studies that will enrich our industry with fresh voices and insight. When women make up 50% of the population and account for up to 80% of purchasing power, it makes financial sense (Blaker, 2022).

2. Energy is weighted towards removing, not resolving gendered communications

In 2017, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) conducted research into gender stereotyping in advertising (Crush & Hollings, 2017). The review found that “overall, adverts were not felt to reflect modern-day society and the depictions of men, women, families and relationships in advertising were felt to be generally clichéd and stereotypical”. ASA introduced new rules to remove ads perpetuating these harmful gender stereotypes (ASA, 2022). Since June 2019, 41 ads (5% of the total) have been reviewed (ASA, Rulings, n.d.).

Three years on, has it improved representation of these groups? Research by The Unstereotype Alliance found that only 7% of ads in the UK today show women, and 9% show men, in non- traditional roles (Alliance & UN Women, 2022). We are still being socialised in the same reductive way. It is worrying to think that these campaigns have been passed between multiple hands, over several months; from brief, to strategy, to script, to production. Approved but not representative. When brands have the power to shape the cultural narrative and set societal norms, why are we still so behind?

I interviewed Tabita Morton, COO of UN Women, who convened the Unstereotype Alliance to ‘collectively use the advertising industry as a force for good, to drive global change for diverse groups’ (Anon, n.d.). She said that “these organisations (hers included) have to go out of business. If we see it as something that needs to be managed, we will never get to a solution. There needs to be an end point (Morton, 2022).” At some point, we have to shift from merely removing outdated stereotypes, like The Body Shop’s removal of ‘anti-ageing’, to proactively resolving them. Creating more ads like BBC Sport’s ‘We Know Our Place,’ which reclaimed a derogatory phrase with a progressive new meaning; a woman’s place is to sell out Wembley, didn’t you know? (BBC, 2022).

Better representation is fundamental to show that women are not one homogenised group. Exasperated by the limited depictions of black hair in video games, UCLA professor A.M. Darke created the Open Source Afro Hair Library; a ‘queer, feminist, pro-black 3D database of afro hair textures and styles’ (@afrohairlibrary, n.d.). This bank of usable assets is accessible to all game developers, so they can be coded into new games from the start, rather than an afterthought (Ira, 2022).

I believe a wider spectrum of female voices in advertising will help to better represent their intersectionality in the communications we dish out. Who better to resolve the social stereotypes in which women have become blindly accustomed, than those who have experienced them?

3. Brands are still too siloed from the CEO

The siloed nature of brands from the rest of the business, exacerbated by the increasing churn of CEO or CMO is holding our industry back (Anon, 2022). Agencies are being dismissed on the long- and-short-of-it debate, as marketing directors feel pressured to deliver short-term ROI (Binet & Field, 2013). Businesses are even forgetting to add marketing to their sustainability plans (Pollack, 2022). Long-term, equitable brand solutions are harder to push through.

Instead, brands prioritise one-off moments or trends which can unsurprisingly backfire. On International Women’s Day last year, brands tweeting the #IWD hashtag got a nasty surprise when their gender pay gap scores were automatically tweeted back at them by a Twitter bot (Lawson, 2021). Cynically, several brands swiftly deleted their posts, rather than address the data. Perhaps because the brand is so siloed from the business, the problem is too far-reaching and difficult to acknowledge – certainly in one tweet.

For brands to be truly successful, they must represent the voice of the customer and speak the language of finance, engaging CEOs and CFOs on the company value that building long-term brand equity can deliver (Barwise, 2015).

I spoke with Danni Mohammed, the founder of Gentle Forces, a creative studio set up to ‘help people, brands and organisations make a cultural shift towards a more fluid, progressive and purposeful way of doing things’ (Anon, n.d.). Gentle Forces led H&Ms latest brand campaign ‘Move'.

She told me that sports brands typically have a very masculine way of framing the notion of movement, but they wanted to reframe it as something inclusive and accessible for all ages and genders. What allowed this vision to be realised was the model in which Gentle Forces ran the process; engaging the male and female stakeholders of the whole organisation, bringing the passion-led insight into the room from the start and collaborating with them on the journey. Crucially, it meant that the brand idea spoke to the financials of the organisation, because those beyond the marketing department were invested in the cause. And it probably helped that H&M is typically a female brand (Mohammed, 2022).

I believe that reaching a more equitable solution in our future can no longer be the domain of brand managers or agencies. These conversations need to happen collaboratively, reaching all stakeholders in the boardroom if we are to produce more advertising that drives lasting, equitable change. CMO in lockstep with CEO.

Enabling these structural solutions by changing behaviour

So now we know the structural solutions, how do we make them happen?

Rory Sutherland prefers starting with behaviour as an objective, because it leaves a ‘bigger potential solution space’ (Sutherland, 2021); ‘Give people a reason and they may not supply the behaviour, but give people a behaviour and they’ll have no problem supplying the reasons themselves (Sutherland, 2019, p. 315)’. Naturally, female-led brands are already leveraging behaviour change theory to create powerful new solutions.

Behaviour change 1: Change the default

We’ve already established that Whitney Wolfe Herd founded a successful company in Bumble. She believed that tweaking an antiquated dating norm could ‘amplify good behaviour and ‘mitigate the toxic behaviour’ (Herd, 2019). This one small tweak empowered only women to make the first move when they matched with a prospective date. This became the defining feature of her app and subsequently recalibrated the gendered norms of an entire dating industry. Eight years on, Bumble is still an extremely profitable company. Their Q3 2022 results showed a 17% increase in total revenue and 36% increase in app paying users (Bumble, 2022).

This changed mass behaviour because ‘the combination of loss aversion, with mindless choosing, implies that if an option is designated as the ‘default’, it will attract a large market share’ (Thaler, 2008, p. 38). Changing the default option to a more equitable one can nudge a large number of people with little cognitive effort.

Remember Gebru and Google? AI is a technology that has increasing control over our lives and if companies refuse to acknowledge the flaws, the default biases will continue to be baked in. It took eight years before Amazon recognised that the default voice of Alexa, its virtual assistant app, did not have to be female. They now provide the option of a masculine-sounding voice (Gartenberg, 2021). After discovering that only 21% of people quoted in the Financial Times were women, the newspaper built a bot ‘to analyse pronouns and first names to see whether a source is male or female’ (Sieghart, 2021, p. 182). This now nudges editors to change the default if they are not featuring enough women in their stories.

If we had more female voices, naturally primed to consider the male-led defaults when a product, brand or advert is first designed, we could shift gendered perceptions on a monumental scale.

What’s more, rather than radical transformations which take time to implement, they can be simple and quick to activate.

Behaviour change 2: Change the context

Context affects the way in which we view the world (Sutherland, 2019). This may be because ‘people don’t know what they want unless they see it in context’ (Ariely, 2009). This can be damaging when we look at the impact of what our cultural context is serving to children. By the age of 6, ‘girls already consider boys more likely to show brilliance and more suited to “really, really smart” activities than their own gender’ (Bian, Leslie, & Cimpian, 2017). In 2018, Mattel set up the Barbie Dream Gap project to help girls achieve their full potential, by changing the context of what they are being shown (Barbie, 2018). Since launching, they have developed a school curriculum on careers and leadership, celebrated a wide diversity of role models and partnered with STEM organisations to get more girls into this field. All contributing to Mattel’s business growth, with Barbie international gross billings up 11% for the last nine months of this year (Mattel, 2022).

One such collaboration has been with The European Space Agency (ESA) and their only practising female astronaut, Samantha Cristoforetti. Their recent joint awareness campaign saw Samantha hosting a Q&A with young girls from space (with her very own Barbie astronaut doll). Since this partnership started four years ago, the ESA has seen more diversity in applications. This year, 40% of those invited to phase two of the application process were women (Hollowood, 2022). A huge shift for an industry sorely lacking in female representation.

If we had more female voices establishing the right environment for girls in the role models and messaging we communicate, we could inspire a whole new generation of voices. If young girls see other girls or women, doing and achieving in what are typically male roles, they will believe they are equally as capable.

Behaviour change 3: Change the copying

Things spread by people copying each other. Not because it’s a better, more informed choice, but because it’s the popular, more social choice. This is how culture works. Your music taste, your hobbies, your politics, are all in fact outside of your control (Earls, 2009). ‘Anti-ageing’ sparked a social norm of age shaming; a behaviour that was copied. This copying starts young and continues into adulthood.

Sexual harassment in public spaces is a behaviour that appears to have been copied, with 70% of women in the UK claiming to have been harassed in a public space (UN Women, n.d.). Morton told me that UN Women’s ‘Safe Spaces Now’ programme seeks to end this copying behaviour. They have led focus groups to understand what women mean by safe spaces and identify areas most at risk, such as festivals and transport. They are working with owners of public spaces, bystanders and activists to create training programmes on how to identify unsafe behaviour and how to intervene. During the UK’s festival season they trained staff and volunteers from eight music festivals to help protect festival goers. Safe Spaces continues to be cultivated through a community of Government, local authorities, public services and transport providers (Morton, 2022). By openly discussing the risks of sexual harassment amongst all types of individuals, not just women, and by spreading the solutions into a wider array of spaces and workplaces, they are shifting the responsibility from one individual to the collective.

If we had more female voices researching and creating communications that champion constructive copying behaviour, we could revolutionise gendered social norms far and wide.

What ties these behavioural examples together is a collective of leaders, brands, businesses and consumers, creating new models of success through changing behaviour. Crucially, it is underpinned by a baseline theory, knowledge and expertise that is equitable, not gender biased. These collective voices are essential to accelerate the behaviour change we need from the bottom-up. When you champion the right voices and embody the right behaviours, you can solve more diverse problems.

Putting the solution into practice

Now I have extrapolated a solution to the inherent bias in our industry, is this relevant for brands in real-life?

I spoke with a Go-to-market manager at Twitch. Gender diversity in gaming is a pertinent issue, especially in a time when ‘tech companies build the world over through Web 3.0 virtual worlds’ (Anon, 2022). We must stop these inherent biases seeping in from the start. We discussed how the gaming industry could benefit from the above behavioural principles.

On Twitch’s platform, female creators struggle to get the same level of engagement as men do (Shrivastava, 2022). A core structural problem is in who is largely designing video games. Despite being enjoyed fairly equally by men and women (Clement, 2020), they are still primarily built by male developers, with only 30% female and 8% non-binary or transgender developers worldwide (Clement, 2021). It is therefore lacking from a greater intersectionality of female voices. Initiatives like Afro Hair Library, as mentioned earlier, curate a database of 3D black hair styles, available to all developers. What if this open-source model was scaled to include a larger bank of female assets, for more groups lacking from representation online, particularly black, queer, non-binary and trans women? This bank could be continually updated and added to, amplified in the right communities, such as the award-winning Black Girl Gamers, who already advocate for diversity, inclusion and equity within gaming (Anon, n.d.). This decentralisation of the default, developer control will help to change the context of what men and women see in a gaming environment. And hopefully serve to encourage greater interaction with female creators, in Twitch and beyond.

We also discussed the importance of creating a safe space online. Recently, a female avatar was groped on a beta test for Meta’s VR app, Horizon Worlds (Milmo, 2022). Female voices are needed to put restrictions and safeguarding in place. For example, women prefer non-verbal communication in games, because exposing their gender makes them more vulnerable, but ‘no game developers have found a way to prevent threats and slurs from being expressed verbally over a headset’ (Fishman, 2022). Similarly to Bumble, what if in-game default options allowed women to choose if they wanted to interact with a male gamer, or automatically block incoming voice messages? Fundamentally though, the inclusion of female voices is essential to socialise progressive copying behaviour when games are being designed, rather than an afterthought.

These examples reinforce that the application of behavioural principles, through a female lens, can make just as much impact in virtual worlds, as the real one.

Conclusion

The bias that I exposed in my course reading list has led me on a journey of discovery. I devoured non-advertising books and alternative sources – articles, blog posts, podcasts, tweets. I tumbled down new rabbit holes. I sought the opinion of my peers. I reached out to my network and was introduced to fascinating female voices who were eager to share their wisdom and further fuelled my passion. This essay represents that collective of insight and ideas, sought by counsel and collaboration. When these female voices, traits and leadership styles are integrated with the foundations of our marketing theory, it enriches our power to affect progressive, behavioural change.

I believe that the addition of these collective voices, already thriving within our industry, are vital to safeguard the future of our craft. Only through a collective responsibility to champion and accelerate them, can we restore credibility from the swelling cynicism, prevent another exodus from our profession and be readier to solve the biggest societal problems impacting our people and planet.

This essay was submitted as part of the IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands. The 2026 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands is now open for applications.

View the full syllabus and submit your applicationThe opinions expressed here are those of the authors and were submitted in accordance with the IPA terms and conditions regarding the uploading and contribution of content to the IPA newsletters, IPA website, or other IPA media, and should not be interpreted as representing the opinion of the IPA.