Winner of the John Bartle Prize for Best 'I Believe' essay in the 2022 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands, Wavemaker's Emily Rich argues that brands need to step back from acting like Big-Gods and should instead become demigods - those who walk among humans but exhibit the divine spark.

'Big-Gods—powerful, omniscient, interventionist deities concerned with regulating the moral behaviour of humans'

The idea of Big-Gods, watchful and judgemental of human deeds, is almost as old as time itself. Whilst brands from Argos to Nike have borrowed visual and mnemonic cues from such mythology, I will argue that the behaviour of many brands has evolved further than this. There has been a shift from metaphorical to literal Big-God behaviour. Expressions of brand self-importance and judgementalism, especially around the regulation of consumer behaviours have emerged. An escalation from borrowing from such mythology towards assertion of a Big-God position, all-seeing interventionist arbiters of morality.

This paper will demonstrate that Big-God behaviour is an ineffective space for brands to communicate and will outline the behaviours brands need to cease. I won’t, however, argue that brands should ‘come down’ to human level as this is also neither desirable nor effective. I will instead propose that to be effective communicators brands need to assume the behaviours of demigods, a concept I will introduce along with three core behaviours brands can adopt to move forward.

Big-Gods: All-seeing eyes

Norenzayan introduced the concept of Big-Gods with a powerful argument; that all-seeing judgemental deities explained the scaling up of modern societies through co-operation and organisation. This is based upon an evolutionary theory of morality that holds that, for cooperation to thrive among self-interested individuals, there must be a credible threat of punishment (Norenzayan, 2013).

A core principle of the Big-God theory was, ‘watched people are nice people,’ and there is certainly evidence that this is true. Gervais & Norenzayan (2012) found that, when primed with the concept of God, people responded in more socially desirable ways. More crucially, studies have found that improved human behaviour doesn’t require an explicit threat of being watched, merely suggestion. For example, Ernest-Jones, Nettle, & Bateson (2010) found that anti-littering posters were more effective in reducing that behaviour if the poster included a set of eyes.

But when did we, as advertisers and marketers, decide that this was an appropriate space for brands to play in? It’s clear the notion of Big-Gods served (and perhaps still serve) a societal purpose, when have consumers ever expressed a desire for brands to act in such a way? And have brands that display this behaviour considered the effect inhabiting this space has on brand-consumer relationships?

For instance, when Hellman’s mayonnaise decided to take consumers to task on food waste, declaring ‘many (of our customers) don’t yet acknowledge that they are part of the problem (Hellmans, 2022)”, did they consider whether this moralistic and admonishing Big-God approach would win hearts and minds (and wallets.)

I’ll outline four Big-God brand behaviours that I’ll argue have had their day, before proposing a new way forward for brands.

The four Big-God brand behaviours:

- Dictating behaviours

- Setting audience agendas

- Leading with lofty purpose

- Holier-than-thou

1. Dictating Behaviours:

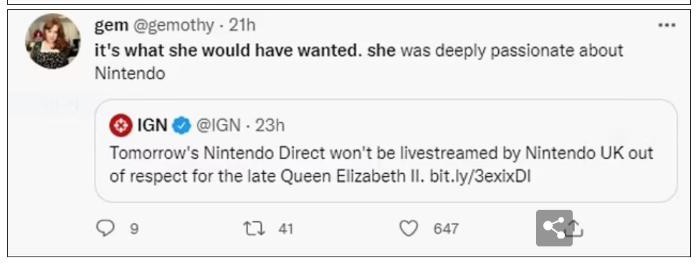

Brands’ peak Big-God moment: #whatshewouldhavewanted

The death of the Queen in September 2022 shone a bright light on brands’ increasingly Big-God behavioural tendencies. It was a period when many took it upon themselves to dictate how their customers should behave.

Peak ridiculousness was hit when the British Cycling Association announced – against official advice - that “As a mark of respect to Her late Majesty, no cycling should take place on the day of the State Funeral,” only to inevitably back-peddle furiously at the public outcry. The Guardian called the instruction ‘worthy of the Stasi’, whilst one furious cyclist asked, ‘Is it ok with you if I don’t follow your ridiculous advice and bike to work? Maybe I can honk the national anthem on my horn?” (Hyde, 2022)

Another brand finding themselves embroiled in a PR nightmare, entirely of their own doing, was Centre Parcs, who decided it was their role to dictate when their customers should and shouldn’t go on holiday. They announced they would be turfing everyone out of their lodges for one night ‘as a mark of respect.’ Obviously, the respect was intended for the Queen but there was none for holidaymakers that had perhaps saved for and looked forward to their holiday. Again, a swift backtrack was made after public pushback.

This, almost hysterical, brand behaviour led to the inevitable social media field day with its own hashtag #whatshewouldhavewanted.

Unfortunately, the joke was firmly on the brands. They had significantly over-estimated and elevated their position in customers’ lives, attempting to dictate behaviours which should have remained an individual choice. A superlative display of Big-God attitude.

2. Setting audience agendas:

Shhh, I can’t hear myself speak!

Such behaviour wasn’t isolated to the Queen’s funeral. Over the past decade, I argue that many brands have become increasingly self-righteous and morally driven, displaying Big-God behaviour as part of everyday comms. Fuelled by social media, the voice of the consumer may be louder than ever, but their actual wants seem to have been side-lined, bulldozed aside in favour of brand decided agendas, often seemingly independent of, or based upon, flimsy insight.

An on-point example is from Bodyform, the sanitary products manufacturer. For their recent campaign Bodyform single-handedly decided not enough people are talking about period insomnia, even giving this its own name, Periodsomnia. They wrote quite the manifesto for people:

"Every night millions and millions of us experience periodsomnia.

We lay down towels, wear extra underwear, hug hot water bottles, run baths at 2am. And kill pain with pills. Or with pleasure.

Because periods never sleep. Even though we're desperate to.

With our wombs bleeding, and our bellies bloating, we're half awake and half asleep.

We're hot and we're cold, we struggle, we snuggle. We toss, we turn, we hold still, praying our pads stay in place. For too many a fear of stains stealing our sleep.

We tiptoe to toilets while our partners, babies or pets sleep blissfully- is that awe or envy we feel?

And all the while, lost sleep slips by - two hours a night, four nights a year, and months and months and months over our lives.

It's time to shine a light on what happens in the dark. For all of us braving the night, united without yet knowing. Because periods never sleep, but why shouldn't we?

Join our quest for sleep #periodsomnia.

Sleep Fearless."

For such a dramatic battle cry, what’s their solution to help their consumers Sleep Fearless? Nothing.

Their ask is for people to ‘join our quest for sleep by sharing the (Bodyform brand) film which is three minutes of content dramatizing Periodsomnia. (Bodyform, 2022)

But more astonishing than having no real solution for the identified problem is the fact that, when investigated, insomnia during periods is a very individual experience. In fact, according to Web MD, only 20% of women ever experience it (WebMD, 2022). Bodyform have hinged their whole communications on ‘shining a light’ on something not relevant to 80% of their audience, and with no solution for the remainder.

Many brands have become so consumed by embodying a dynamic ideology that they have lost sight of what matters to the very people they want to sell to. By deciding what should be on the public agenda (menopause seems to be having a hot moment here) brands have slipped firmly into Big-God territory.

3. Leading with lofty Purpose:

‘Honestly, get over yourself’

‘One might forgive advertisers and marketers falling for the temptations of grandiosity… we yearn to amount to more. To spark movements, promote causes, create better futures, ignite conversations, and yes, make the world a better place, one virtuous, purpose-driven (but still oh-so-profitable) corporation at a time.’ Weigel (2020)

In mid-2020, communications agency Zeno published its influential Strength of Purpose study, claiming it provided ‘unequivocal proof that companies leading with Purpose will prevail’. It contained impressive statistics such as, ‘94% of consumers say it’s important companies they engage with have a strong Purpose,’ and consumers are ‘4 x more likely to purchase from these brands (Zeno Group, 2020)’

It’s no surprise marketers snapped to attention. But people can be fickle creatures, prone to portraying themselves as more virtuous than they perhaps are. Studies supporting this point to a likely ‘intention-action gap’ existing between what people say they will do and what transpires. IPSOS data clearly shows this gap, whilst 62% of people agree they ‘support brands that do more good than harm to society’, only 14% strongly agree that they tend to buy these brands more (Ipsos, 2021). So, the intention may be there, but the commitment is lacking.

However, not only do consumers not convert from intention to action when presented with purpose-led strategies, often they aren’t even aware of what purpose renowned brands are behind. A study from Do Something Strategic found only 12% of younger consumers had top-of-mind associations between brands they knew and their causes. Providing a list of these social causes only increased these associations to 24% (Cision, 2019). Proof indeed that unless you ‘do a Patagonia’ a brand’s big Purpose is likely to go not only unrecognised but also be uninfluential.

Whilst brands need their own moral compass, they shouldn’t be attempting to define ours. As Marina Hyde in The Guardian voiced, ‘Honestly, get over yourself, you’re in retail. Just sell me your crap and be on your way (Hyde, 2022).”

4. Holier-than-thou

Do-gooding isn’t doing brands any good!

It’s a scientifically proven fact that people have an involuntary aversion to ‘do-gooders’. Research by Parks and Stone (2010) found that in a group-game where participants had to show their monetary public giving, as expected they kicked out those who gave too little from the group – but also, surprisingly, those who they deemed gave too much. This finding has been replicated, leading David Robson, the social scientist to write, ‘this seems to emerge early in life (and) it seems to be present in most cultures, suggesting it may be a universal tendency (Robson, 2021).”

If we translate this to brands, we can immediately see how those that adopt a preacher style posture may rub people up the wrong way too. Birds Eye learnt this the hard way with their Welcome to the Plant Age advert. Assuming a clear ‘holier-than-thou’ approach the brand said it would ‘challenge consumers’ beliefs and encourage them to reassess their current eating habits’ (The Grocer, 2022)

Unfortunately for Birds Eye, many consumers didn’t interpret the subsequent advert as encouragement, instead they saw it as shaming. Featuring a small child challenging her mum on why she doesn’t cook plant-based food they posed the question, ‘“Is it because you fear change and you’re scared to try

something new?’ This admonishing tone led to many calling Birds Eye out on social media, ‘No I don’t fear change, Birds Eye stop telling people what to do.” Another posted that the advert has a ‘complete lack of anything to make you want the product (Reddit.com, 2022).’ This latter post is astute in its identification that Birds Eye doesn’t appear to be attempting to sell their food based on its appeal but rather by challenging consumers on their moral approach to eating.

Psychology professor Pat Barclay, who has conducted a number of studies exposing negative attitudes to ‘do-gooders’, says “Most of the time we like the co-operators, the good guys. We like it when the bad guys get their comeuppance. But people will hate on the really good guys. It is essentially human nature (that) we are suspicious and unwelcoming towards those who appear to be better or holier than we are (Ratner, 2018).”

Moving on from Big-Gods: Why brands need to harness and create demigod energy

“We need to stop interrupting what people are interested in & be what people are interested in.” Craig Davis (n.d)

Meadows et al (1972) found that people are primarily concerned with matters that affect those close to them, and only over a short period of time, stating, “The larger the space and the longer the time associated with a problem, the smaller the number of people who are concerned with its solution.”

Ultimately very few have a global perspective that extends far into the future, and crucially this means that brands primarily communicating through behaviour-dictating stances on lofty issues is likely to fall on brand-deaf ears.

This paper posits that brands need to step back from their increasingly explicit Big-God behaviour. Consumers might want to add mayo to their BLT without being openly accused of contributing to food waste. Setting consumer agendas, leading with lofty purpose, dictating behaviour and being a do-gooder are ineffective strategies for communications.

With the attention-economy saturated and the purpose-economy wearing thin, I believe that there is a new evolving space for brands to communicate with audiences. As marketers and advertisers, we need to shift brands, from a Big-God to godlike status. I term this Demigod.

Demigod: Someone who has the divine spark. Figuratively, it is used to describe a person whose talents or abilities are so superlative that they appear to approach being divine.

Demigod behaviour is not a devaluation of brands. Demigods have abilities that surpass mortals, but they can also cross domains that gods cannot cross, making them the ultimate communicator. (Graves, 2011).

I’ll outline three key behaviours that will enable brands to move into more successful communication spaces with audiences

- Instilling awe

- Elevating the everyday

- Lightening the mood

1. Demigod brands instil awe rather than bore

Psychologist, Kirk J Schneider determines awe as “humility and wonder, or sense of adventure toward living…the capacity to be deeply moved and to experience the fuller ranges of being alive (Schneider, 2016).” Awe is the antithesis of day-to-day human concern, the quick fix, speed and efficiency that brands so often focus on, but it also sits clearly away from controlling and authoritarian Big-God behaviours.

Creating a sense of awe can be a powerful tool for brands in their quest to engage with consumers. This is because it involves connection with the bigger picture of living and a sense of participation in the world. Importantly to induce awe you also need to acknowledge humility, something Big-God brands lack.

And experiencing awe is a very desirable state for people. Studies have shown that those who feel awe, relative to other emotions, felt they had more time available, were less impatient, more willing to help others, and had a greater boost in life satisfaction (Rudd, Vohs and Aaker, 2012).

Experiencing awe also helps people process cognitive information more efficiently and effectively – an opportunity to have more in-depth conversations with consumers (Gottlieb et al 2018). What brand wouldn’t want that kind of deeper connected relationship with its audiences?

Schneider, points out that awe ‘first and foremost derives from caretakers…a mentor able to model life (2016).’ This is where the opportunity for brands sits. Awe also helps enhance collective concern to improve the welfare of others, meaning, ironically, inducing awe may help brands achieve some of their loftier purpose goals that haranguing does not. Hellman’s may have more success reducing food waste by bringing to life the awesome might of nature being harmed, than it does by simply telling people they are part of the problem.

Harvard Business Review determined that ‘perceiving something one has not seen before but that was probably always there’, is one way of inducing awe (Fessell & Reivich, 2021). Pernod-Ricard’s Spanish campaign is a good example of this. Working with the insight that humans avoid thinking about the time they’ve left to live and therefore put off the things they want to do, led to them asking one question - ‘if you knew exactly how much time you had left with the people you love, would you keep on living the way you are?’ An algorithmic calculator predicted exactly how much time people had left with their loved ones in terms of days and hours. The stark reality of their valuation of time created a series of emotional portraits that transcended traditional advertising and was, quite literally, awe inspiring, bringing to life something that was always there but had never been seen. The campaign was a huge success winning a Cannes Gold Lion for effectiveness (DandD, 2020). It was awesome.

2. Demigod brands elevate people out of the every-day rather than reflect it

In 1975’s seminal article, “Marketing Myopia” Levitt described the issue of ignoring customer needs and desires – “People don’t want a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole! (Levitt, 1975, p. 8)”

Or for a more modern take. “For a business to be truly customer-focused, it needs to ignore what people say. Instead, it needs to concentrate on what people feel” ― Rory Sutherland (2019, p.86)

In Maslow’s seminal Hierarchy of Needs, after basic safety and physiological needs are satiated, we have the need for interpersonal belonging and relationships with others, which has been identified as an evolutionary instinct (Maslow, 1945). Many brands want to be leaders amongst consumers, and this has led to Big-God behaviours. But does this make sense? Not if you consider a 2019 study on leadership and likeability which showed that people tend to rate leaders based on their personal liking of that leader, rather than the leader’s actual behaviours (McAllister, Moss, & Martinko, 2019). Therefore, translating this to brands, one that is likeable is likely to be more influential than a well-behaved brand.

As we head towards our first Christmas during the current cost of living crisis there’s been a lot of discussion in the advertising community (and beyond) about appropriate tone. Campaign asked the question, ‘do the current crop of Christmas ads match the mood of the nation (Campaign, 2022)’ However, I’d argue that great brand advertising doesn’t need to hold a mirror up to exact circumstance to be successful, it needs to transcend that. It needs to find the spaces of connection where it can elevate the everyday, becoming a likeable character in the process.

Tesco’s Christmas 2022 advert, ‘The Christmas Party’ lands this spot on. They commissioned their own research that showed a third of people in the UK think Christmas is more important than ever this year because of the cost-of-living crisis. Their chief customer officer Alessandra Bellini said: "We understand that it is a tough time at the

moment, but our research shows that there is even more excitement around [Christmas] than usual (Campaign, 2022).” Therefore, instead of creating an ad focused on price or trying to reflect a sombre mood, it cleverly nods to the troubled times we find ourselves in, yet at the same time elevates above it by focusing on how Tesco can help customers address the ‘national joy shortage.’

Independent data from marketing consultancy System1, who have measured the impact of this year’s Christmas ads on consumers, confirms the success of this approach saying, “It’s easy for comfortably off commentators to criticise more typically festive fare as inappropriate in a cost-of living crisis (but) ordinary viewers don’t want ads to mirror their struggles – more than ever, they’re responding to ads that make them feel a bit of happiness in a tough time. (Campaign, 2022)”

3. Demigod brands lighten the mood instead of setting agendas

“Don’t treat your subject lightly. Don’t lessen respect for yourself or your article by any attempt at frivolity.” So said Hopkins in the 8 million selling book Scientific Advertising (Hopkins, 1923).

He may have been right then, but this certainly doesn’t hold true now. The British love people and things that aren’t perfect and that can laugh at themselves. They love the silly, the self-depreciating, the underdog. It’s why they vote for Ed Balls on Strictly or send odd little songs about sausage rolls to Christmas number 1. It’s why they unashamedly wear Greggs’ clothing.

But humour itself is not a silly practice to engage in. In his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, neurologist, psychiatrist, and Holocaust survivor Victor Frankl said, “Humour more than anything else in the human make-up, can afford an ability to rise above any situation, even if only for a few seconds. (Frankl, 1946)” This belief isn’t only anecdotal, it’s been proven that social laughter increases pain thresholds, literally altering physiological response (Dunbar, et al., 2011).

Jeremy Nicholas, a BBC broadcaster and British humourist argues, “A lot of leaders spend all their time thinking about being a great leader and thinking, ‘Oh no, I can't be funny. I’ll lose credibility’. You don't have to be funny, just be playful (Nicholas, 2022).” This advice sits equally well for brands, and this has been borne out in research. In Orlando Wood’s, Lemon, when making the case for humour he shares statistics that show two thirds of adverts don’t use any form of humour, yet Binet and Field’s IPA database work has shown that brands that do have far more significant business effects (Wood, 2019).

ITV in it’s What Unites a Nation study showed Brits prefer to balance challenging times with moments of collective spirit, fun and laughter, in fact 74% felt that this is what defines us as a nation (What Unites a Kingdom, 2022).

One brand that has elevated itself to demigod status using self-aware humour is Duolingo. Users of the language learning app had long amused themselves creating memes around the aggressiveness of the company’s owl character who admonishes users daily when they don’t practice. In 2020 Duolingo took this on-board and created a Duolingo/Angry Bird mash up for Tik-Tok, showing what might happen if you let Duolingo get really angry. That same year it reached 500m downloads, which was up 30% YOY. In 2021 it was set to surpass its 2020 revenue ¾ way through the year (The Drum, 2022). Humour isn’t frivolous, it generates income.

Applying demigod principles

Applying the demigod principles to the previously discussed Bodyform campaign we can see how the shift in brand behaviours might look. Periods are sometimes, rather old-fashionably, referred to as Mother Nature because they are a fundamental process in the birthing of life. This in-itself is an incredibly awe-inspiring concept the brand could draw upon within communications. Shifting from a portrayal of inconvenience and negative experience to periods as a fundamental pivot of life, part of something bigger than us, instilling awe.

Alternatively, considering the latter two principles, whilst not suggesting a throwback to the days of women giddily roller-skating in white shorts, there’s no reason that functional brands such as Bodyform can’t portray a more eclectic or upbeat perspective for consumers.

The current Periodsomnia campaign has swung so far from its famous (and incredibly unforgettable) ‘Woah Bodyform’ era it now focuses almost solely on negative human experience. It doesn’t have to be this way. For a great example of incorporating both principles of lightening the mood and elevating the every-day, take Flo organic tampons. Their ‘no more period dramas’ campaign cleverly played with the hugely popular trend of TV period dramas such as Downton Abbey, Poldark and Bridgerton. Laugh out loud funny, the advert topped Kantar’s effective ads for the month it aired on TV, and the digital content was incredibly shareable for users, with a compelling reason to so do.

From Big-Gods to Demigods conclusion

Throughout this paper I’ve argued brands need to step back from acting like Big-Gods. By adopting the attitude of moral North Star, brands have leant into displaying lofty purpose-leading, agenda setting, behaviour dictating and holier-than-thou behaviours, that simply aren’t welcome. I’ve gone on to propose and outline three behaviours brands can deploy to behave like demigods; instilling awe, elevating the every-day and lightening the mood.

Demigod brands straddle heaven and earth. They walk among humans but exhibit the divine spark. The humanity of a mortal, but with the touch of a god.

The 2024 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands is now open. Find out more and apply now.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author and were submitted in accordance with the IPA terms and conditions regarding the uploading and contribution of content to the IPA newsletters, IPA website, or other IPA media, and should not be interpreted as representing the opinion of the IPA.