In her 'I Believe' essay for the 2019-20 Excellence Diploma, Vizeum UK's Grace Letley explores a brand's relationship with trust.

The era of institutional trust is fading. Trust in advertising is declining. Trust – the very foundations of brands – is redistributing. Increasingly, it is individuals who are the creators, the context and the authority on trustworthy transactions. As validation and verification flows away from authorities and into communities, brands should not seek to reverse the trend but reconfigure for it. In this new era, trusted brands are built with people rather than for them, against the destablising effects of the digital age. I believe that by creating shared autonomy; shared realities and herd immunity, brands can simplify the complexity of decision-making in a world full of (deep) fakes. Welcome to the new brand circles of trust.

Without trust a brand is just a product and its advertising is just noise.

This is the provocation spurring on the Advertising Association’s 'Arresting the decline of public trust in UK advertising' report: phase 1 of a longer-term action plan seeking to drive systemic change (Weed et al. 2019).

I agree declining trust poses an existential threat for brands and advertisers and systemic change is required to address it but I disagree with the diagnosis. I believe the nature of the changes in consumer trust run far deeper than surveys can report and the implications require a revolutionary rather than evolutionary approach to brand building and advertising.

I will argue distrust is not the enemy; the so-called 'trust crisis' is not the problem; in fact, people are trusting more easily than ever before. The real trust crisis: "Consumers don’t NEED to trust brands, they have too many options, too many platforms, too many influences." (Quoting Zhang, cited in Jones, 2019).

With Shirky’s principle looming large, the question for brands is, therefore, not how to arrest the declining public trust in UK advertising but rather: how do we build brands in an era of distributed trust? More specifically, how do we build brands as the antidote to the complexity of decisions in the digital age with, rather than for, people? (Shirky’s Principle cited by Kelly, 2010)

I will outline the reasons for my diagnosis, the opportunity this inflection point brings and the consequences of inaction. I shall recommend brands reinvent themselves as the antidote for the complexities of decision-making in the digital age, specifically: the burden of autonomy, the disappearance of shared realities and the threat of disinformation. I will conclude with the steps brands need to take in designing for a world where people, not institutions, are the providers of brand context.

Brands as 'Trustmarks'

Brands originated as symbols of trust: 'Trustmark'. A guarantee that the product, or service, carrying the brand would consistently deliver the quality promised by the reputation it had built. Brands enabled people to confidently transact beyond their immediate circle of trust – people known within the community with a reputation to maintain. (Yakob, 2015).

Brands learned that investing in advertising – particularly expensive, fame-driving advertising – was an effective means of signalling trustworthy status. It creates what Rory Sutherland terms, "reputational skin in the game which acts as a commitment device and creates trust." The more a brand is perceived to invest in its reputation, the more it has to lose from under-delivering. (Sutherland, n.d)

As choice became more prolific and rational details of differentiation became almost impossible to discern, brands stepped up to help consumers shortcut their decisions by representing, "clarity, reassurance, consistency, status, membership, everything that enables human being to help define themselves" (Olins, 2005).

Trust in context

Is trust still important for brands today? It depends… Yes, insofar as "trust is fundamental to every action, every relationship, every transaction." (Botsman, 2017). Is it important that I trust Coca Cola not to poison me? Yes. Is trust the reason I choose Coca Cola over Pepsi? No. Clearly, some categories are more trust-sensitive than others. As the internet of things bring brands directly into our homes to monitor our consumption, behaviours, doorsteps and conversations, trust is going to become an increasingly important currency of the future.

Trust is as nuanced as it is oblique. For example, as Sir Ian Chesire, Chairman of Barclays UK points out, a bank can have vastly different levels of perceived trustworthiness depending on whether the researcher asks about trust in the CEO or the local bank manager (as cited by Phillips, R, 2020). Brands can no more solve for trust than they can complete happiness. Trust can’t be aimed at or measured directly. In order to act practically on any matters pertaining to trust, it must be regarded in service of consumers, in the context of the bigger picture.

Trust is not universally declining, it is re-distributing

There is a trust problem but it is not in terminal decline – is the prognosis of the 'Trust: The Truth?' IPSOS Mori Report. (Page, 2019) There are important nuances to the trust debate: Trust in business declined twenty years ago, remaining flat since then. (Phillips, 2019) Trust between people in Great Britain is rising: +7pp in the past decade.

The critical turning point today, recorded by both IPSOS and The Edelman Trust Barometer 2020, is the trust inequality between the masses and the informed elites has never been greater. Institutions are seen as unfair, serving the needs of the few, not the many. (Page, 2019; Bersoff et al, 2020) It is this context, supported by the actions and behaviours of consumers that is pivotal to the trust debate today. We are now at the dawn of a new era of distributed trust. "Trust that used to flow upwards to referees and regulators, to authorities and experts (…) is now flowing horizontally, in some instances to our fellow human beings and, in other cases, to programs and bots "(Botsman, 2017).

Dovetailing with Credos’s report of declining trust in advertising, Nielsen’s Global Trust in Advertising report confirmed, the most credible advertising comes straight from the people we know and trust, eight-in-ten trusting the recommendations of friends and family and two-thirds trusting consumer opinions posted online. (As cited in Weed et al, 2019 and Anon, 2015) This shift has been driven, at least in part, by the democratization of content creation and distribution. As Yakob put it, "Social media took any personal experience of disconnect between brand promise ad deliver and amplified it out to the masses". Consequently eroding trust in brands and advertising overall. (Yakob, 2015). Pre-internet, it would take a marketing team’s incompetence or a founder’s indiscretion (Gerald Rattner springs to mind) to trigger the demise of a brand. Nowadays, a tweet from Kylie Jenner can knock $1.3bn from Snapchat’s market value. (As cited by Vasquez, 2018)

We are facing a new era in which the centralised, institutional trust brands were built on is breaking down. We cannot hope to rebuild it, instead we must redesign brand-building for an era of distributed trust in the digital age.

The opportunity this inflection point brings

It used to be that people were born as part of a community, and had to find their place as individuals. Now people are born as individuals, and have to find their community.

From modest 'trustmark' origins to culture-shaping icons, the twentieth century witnessed brands traverse the hierarchy of Maslow’s needs in service of consumers, demonstrating how deeply people are willing to integrate brands into their lives. The 'consumer tribe' and imagined market communities are embraced in the absence of deeper-rooted relationships we had as 'villagers of the past' (Harari, 2015). In our new hyper-connected era, brands can strive for the very pinnacle of Maslow’s pyramid for a 'transcendent kind of togetherness' against the burden of individualism. (Quoting Bishop, as cited by Garber, 2017)

The last time we hit upon an inflection point like this with five vectors of transformation and historically low trust, it was a revolutionary opportunity for brands which, "quite suddenly burst out from the narrow, strictly codified world in which they had been bred" (… and became…) "a commercial and cultural phenomenon of unparalleled force"(Olins, 2005). I believe this next era could be just as seismic in its reinvention of brands, bursting out from the confines of centralized institutional control to embrace joint ownership of the brand and its narrative.

Brands are shortcuts through complexity

"Brands are not the rich sources of differentiation marketers like to think of them as, but shortcuts through the complexity of decision-making" (Leslie, 2015) The digital age has brought with it a seismic shift in the complexity of decision making for consumers today, along with unprecedented access to other people’s views, actions and trades.

This should be a golden opportunity, yet there is mounting evidence of this brand power waning as consumers turn instead to each other for navigation. Why should people trust brands to guide them when they can be guided by each other?

The consequences of inaction

Brands are already losing out to other forms of social proof as influential shortcuts to bolster confidence in their transactions:

- Seven-in-ten say they will try a product or service if it has a good review (GB population, Global Trends Survey 2016, as cited by Shipton, 2017).

- It is estimated online reviews influenced £23bn of transactions in the UK in 2018, matching UK ad spend that year (Competitions and Markets Authority, 2018 as cited by Boxer and Croker, 2018; Weed, 2018).

- In 2013, academics Zervas and Luca concluded that an extra star on Yelp caused the revenue of a business to rise by 10 per cent. They also found at least 16% of reviews online are fake (as cited by Moore, 2020).

Wally Olins’ statement, "We like brands. If we didn’t like them, we wouldn’t buy them" (Olins, 2005) poses a stark reminder when set against a recent report from consumer watchdog, Which?, showing customers voting with their wallets and choosing unknown entities over recognised brands at a rate of 4 to 1 in online marketplaces, bolstered by Amazon Choice logos and peer reviews.

"Money is the currency of transactions; trust is the currency of interactions. Without trust, a business becomes purely transactional over time." (Botsman, 2020) Brand must reinvent as shortcuts for the digital age by rising up against the new complexities of decision-making it brings.

Driving forces behind the complexity of decision-making in the digital age

1. The burden of autonomy:

Choice is paralyzing. We believe that we want the freedom to make our own decisions, but too many choices make us anxious and leads to counter-intuitive behaviour.

With the internet came access to the world’s information and gave rise to individualism. It’s broken down barriers to trade, direct to consumer products and services have flourished along with The Sharing Economy. Today we can transact with individuals around the globe as easily as retailers on the highstreet. Except now we find there is too much information to make an informed choice. Transactional leaps of faith have grown larger and daily life demands we make them routinely.

Today people are more trusting than ever: We get into cars with strangers (Uber), invite unknown families into our homes (AirBnB) and book holidays based on the recommendation of a person (or bot) whom we have never met (TripAdvisor). These businesses are, of course, brands in their own right but the social proof baked into the networked communities are critical to their success. Our growing ease with trusting strangers is creating people-powered market places and is directly responsible for the growth of the Sharing Economy, estimated to be worth £140 billion by 2025 (PWC, 2016)

2. The disappearance of shared reality

The monoculture has not disappeared altogether this decade but like a Dwarfstar it has shrunk and its power is much weaker.

An abundance of content available to us on-demand combined with increasingly targeted distribution capabilities has disbanded our shared realities. The context by which we navigate the world has gradually fallen away, taking with it the comforting cues & shortcuts our lazier, System 1 thought processes used to make intuitive decisions. (Kahneman, 2012) What one person sees, is sold and experiences in any given day isn’t the same as the next person’s. Watching TV used to be a social experience even when viewed alone because everyone would be watching one of the 4 same channels. It works because it happens between people. The synchronicity of content consumption has diminished. This matters to brands because one of the superpowers of broadcast channels is not just the audiences you reach but those that overhear the message. It is this that generates reputational skin in the game for brands and a security blanket of social connection for consumers.

3. The threat of disinformation

Technological developments mean we soon won’t be able to believe what we see or hear. Also known as 'the vanishing point of human authority' (Harris, 2020). There are 14,678 Deepfake videos already out there, identified by Deeptrace and their sophistication is growing daily (cited by Thomas, 2019). Why it’s a problem for brands: any brand could have a deepfake attack released against them and with only the word of the institution against it. There is no simple answer to the potential catastrophes of deepfakes but one promising area for brands promoted at a UK Behavioural Insights Team Conference is the idea of strengthening people’s mental antibodies in order to help society build a 'herd immunity'. In a prevention is better than cure approach that helps people understand the mechanics of the fakery through tacit access. (Sander van der Linden, cited by Thornhill, 2019) Gregory, Witness Programme Director supporting activists in ethical use of technology around the world, supports a similar line of defense, recommending media literacy is sought by asking three questions: ‘Who does this come from? Where does this come from? What corroborates it?’ (Gregory, 2019)

There has never been a more important time to have diverse communities of trusted voices to support disinformation. This imperative is only going to increase. By building brands with rather than for people, brands create the conditions for trust to grow and new people-based contexts for validated choices in this era of distributed trust.

The New Brand Circles of Trust

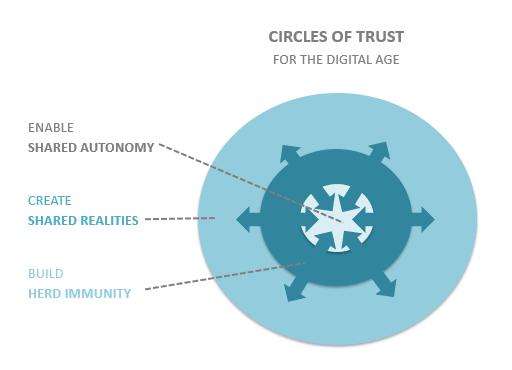

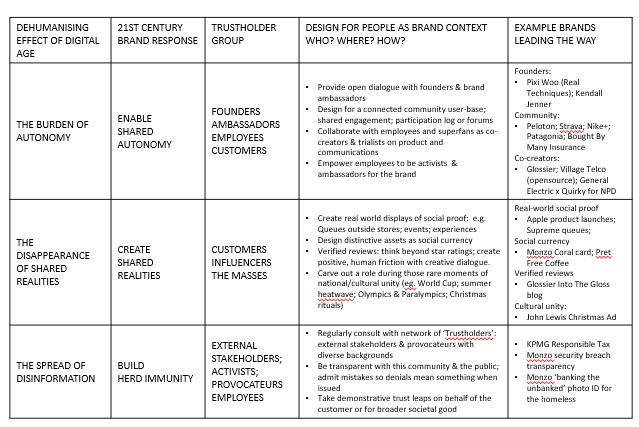

In this increasingly uncertain and complex environment, I propose brands are designed for intuitive navigation. Brand trustworthiness will be signaled in the circles of trust it builds across three essential communities:

Who does it come from?

The 21st century cultural need for brands to serve is to enable shared autonomy by designing brands with communities, for communities.

Where does it come from?

The role for advertising and communications will be to create shared realities by embedding brands in the cultural and communal contexts of your own making as well as those rare monocultural and community specific occasions.

Who corroborates it?

The measure of brand strength will like in a brand’s ability to build herd immunity against disinformation with 'Trustholder' networks.

Diagram 1, below, illustrates how these different collectives interact. Diagram 2, outlines who needs to be invited into each circle of trust, the key principles of engagement and example brands that are already entering into this space.

How Trust-Circles interact

The 'Trustholder' network will naturally feed into and inform the core brand creation; with conclusions reached via positive friction between these communities impacting directly how the brand is designed. This may play out through product innovation, supply chains, activist stances or campaign-based communications. It is also vital these diverse sets of stakeholders have their opinions overheard by broader audiences, that these conversations and debates show up in shared realities beyond the confines of the community. It is these overheard conversations that build the brand antibodies against the threat of disinformation. (Inspired by McCormick, 2019)

Where once brands were the ‘trustmarks’ and advertising provided the cultural and social context from which confident decisions would be made, it is increasingly now people who are the trustholders and the trusted contexts. The new brand circles of trust will be designed with, communicated amongst and verified by people and their diverse communities.

Concluding remarks

The changing nature of trust does not have to be a time of crisis for brands, rather it can provide a land of opportunity. As Levitt reminds us, “Businesses forget that meetings the customers’ needs are the problems to be solved.” (Levitt, 1975) The existential threat posed by changes in institutional trust can be reversed, not by aiming at trust directly but instead, reconfiguring brands to do what they have always done but in a new context. I recommend this is achieved by building brands as the antidote to the disconnection, disappearing contexts and disinformation the digital age brings. In doing so, brands can regain their status as feel-good shortcuts through the complexity of decision-making. Validated not by the authorities but by its communities, building trustworthiness in the process. So ask yourself, how is your brand designing for the new brand circles of trust?

Grace Letley is Managing Partner – Strategy at Vizeum UK. This essay earned a distinction as a part of the IPA Excellence Diploma. The 2026 IPA Excellence Diploma in Brands is now open for applications.

View the full syllabus and submit your applicationThe opinions expressed here are those of the authors and were submitted in accordance with the IPA terms and conditions regarding the uploading and contribution of content to the IPA newsletters, IPA website, or other IPA media, and should not be interpreted as representing the opinion of the IPA.